Barry Purves – Respect the Puppets! Part Two

When Barry Purves gave a talk to the audience gathered in Halifax for Creative Calderdale (Part One of “Barry Purves – Respect the Puppets!” can be found here), he began explaining the nature of working with puppets, particularly how their rigid physicality can sometimes add creative complications when a character simply cannot get in the pose as planned in the storyboard. This caused him to explain how he would have to spontaneously adjust the puppet in a way that both accomplished the intended performance as well as worked for the puppet. He said that you cannot force a puppet to do what it does not want to do. He began repeating, “Respect the Puppets! Respect the Puppets! You must respect the puppets”. Not only does Barry Purves have great respect for the art form, but also he displays respect when he is animating a puppet. This is certainly the case with the second of Purves latest work we are highlighting “Tchaikovsky – An Elegy”

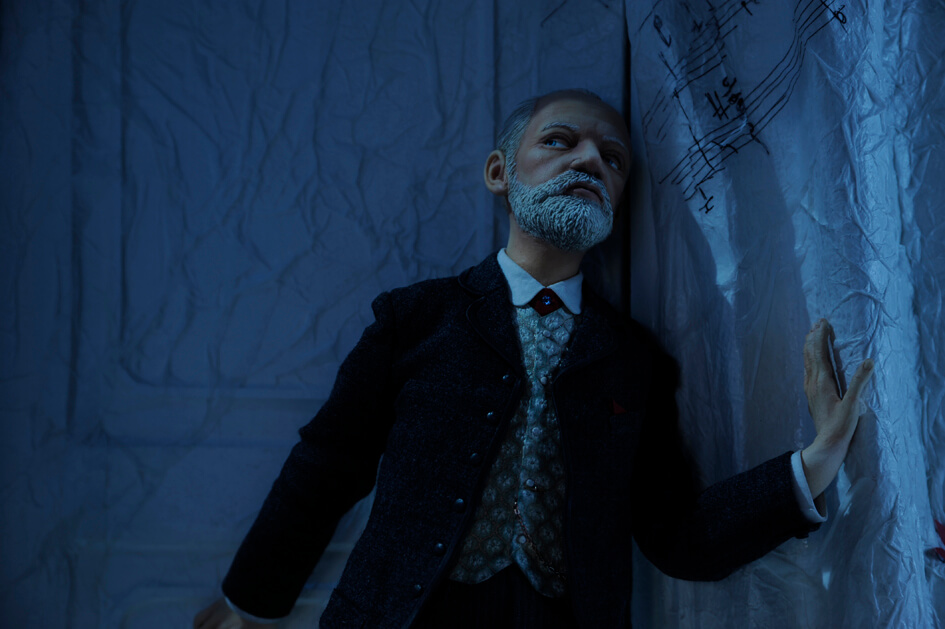

Although the film is not strictly autobiographical in the traditional sense, it seems to take place in a fictional room in which the composer is forced to re-live his life through encounters with his past demons, as well as quotes from his life taken from his letters, accompanied by sections of his music. Even if you are not overly familiar with classical music and would prefer to call Prokofiev’s Dance of the Knights “the theme from The Apprentice” you won’t feel out of touch watching this film. I admit to not knowing or caring a great deal about the composer before watching this film, but after 13 minutes I felt really sorry for him and wanted to learn more. When a film makes someone want more, it must be doing something right.

The film displays both a love of the craft and a love for the work of the individual it is portraying. A great deal can be learnt from the relationship between the animator and the subject matter. When Barry Purves took on Pyotr Ilych Tchaikovsky he didn’t just take on his music and moved a puppet that looked like him, he also took a journey of discovery to Moscow and brought him closer to a musical composer that he has held a fondness for since he was 4 years old.

Do you still have the Tchaikovsky puppet? When I have seen you with Tchaikovsky you carry him around like a child, you seem to have a bond with him.

Yes, I have him with me, though he has been on display for a while at the National Media Museum. Since the film I have been asked to do a few live workshops with Tchaikovsky, I did one in Poland in front of a big audience but I only had 45 minutes to create something and I didn’t want to do that with Tchaikovsky. I can’t do something silly or trivial with him. On Plume we were nearing the end of the shoot and we had finished filming with “the shadows” when I came in one morning to find that they had been animated, but not by me. What was animated was quite out of character which rather upset me. That, I admit, is me being overly sensitive (in a way only animators would understand), but you do have to be true to the characters. I wanted to give the puppet of Tchaikovsky dignity, quite a hard quality to achieve, when we are so used to puppets behaving comically. There was one shot towards the end of the shoot where, we all thought, that he had lost his dignity. It was only 4 seconds of ‘Swan Lake’ inspired wing movement, but he looked rather more like a turkey. It didn’t work so we got rid of it, which is all that was cut from the film. It is better now though as Tchaikovsky keeps his dignity.

What I am pleased with both Tchaikovsky and Plume is that you can see the thought process of the puppets, even with quite limited facial expressions. Our primary role as animators is to externalize the internal thought process of our characters, whether they be small objects or complicated puppets. I like the idea that I give puppets life and then rather cruelly abuse that life and make them suffer. They all suffer. Tchaikovsky cries and the Plume character bleeds. It’s a satisfying irony with puppets; that you give them life and then play with it, be cruel about it and take it away. I think all the characters in my films are tormented and I quite like tormenting them– perhaps it is cathartic for me. It’s not a particularly common emotion in animation.

How did Tchaikovsky come about as a project, is it always something that you had wished to do?

I have loved “Swan Lake” since I was about four years old. I may have seen Swan Lake live around 40 times, and never tire of it, especially with the idea of an alternative, more liberated way of life, as represented by the swans. We all need that escape. I love it as a story and I love the emotion. For me, the last 5 minutes is probably the most moving, well dramatic piece of music ever written. I can’t sit down when it’s playing! I cry so much! I got to know Tchaikovsky quite well and I went to his house. To actually be in his bedroom and be able to touch the furniture and his piano was as close as I could get to meeting him. I had a something of an emotional meltdown whilst I was there. He is such a rich, tragic character. He certainly was not without humour and joy but oh he was troubled and so full of self doubt. To work with music like his is a gift. How the project came about was through Irina Margolina, a Russian producer, who liked my films and some time ago she invited me to Moscow to direct a play about Jascha Heifetz, the Jewish violinist.

The idea was to do it with Moscow’s leading actor, but I knew little about the Jewish faith; I could not speak Russian; and certainly could not play the violin, or speak Russian, so I thought I’ll just do it – how far out of my comfort zone can I go! I had agreed to do it but sadly circumstances changed and we lost the momentum. Irina and I stayed in touch. She started a series called “Tales of the Old Piano” about classical composers. The others in the series are mainly CG and are filled with colourful backgrounds and multiple characters which are easier to accomplish in CG. For a stop motion film, though, the budget was small and only allowed me a single puppet, and one set – but as is so often the way, these restrictions also force inspiration. I only had 13 minutes to do justice to Tchaikovsky. I had to think about bringing in the other necessary characters in his story, but without physically building them. Luckily, photography was reasonably sophisticated at the time, and his life was well documented. Projections seemed an appropriate and practical way to feature these characters, and led me down the path of a narrative about memory.

Like most of my films, such as Next, this shows the protagonist justifying their life and existence (is that me? Who knows? Yes it is!) In all my films apart from the Wind in the Willows, there is always someone watching and judging. Screen Play had the narrator, sat outside the action, In Rigoletto there are the two assassins guiding the action. In Achilles there is the chorus watching and guiding the action. With Gilbert and Sullivan, it is D’Oyly Carte. So, that’s a common theme of my films; being judged. Also the whole obsession about the creative process, with the creation being an extension and honest reflection of the creator would give a therapist much cause for thought. This and the constant self doubt lead the Tchaikovsky film to become a not very subtle cipher for much of my life. He is certainly someone I can understand, I have never tried to commit suicide as he did, nor have been to such extreme depths, but we certainly share many character traits, foibles, and weaknesses. When Irina asked me about three years ago in Annecy to pick a composer for the series, we each wrote a name down on a piece of paper. We both had Tchaikovsky! I did have a standby just in case which was Handel, but I think the complexity of Tchaikovsky really attracted me as well as the music. I like the torment and the anguish of Tchaikovsky. It is basically Next, but with added anguish!

Like “Next” you seem to have a great passion for the character in question, are there any other figures you would wish to animate?

Yes! But I have been beaten to it. I have been obsessed with Georges Méliès for so long and unfortunately Scorsese has got there before me with “Hugo”. I don’t know whether or not that will stop me, I wanted to make a film about his mad joyous genius and his unfortunate abandonment. He was reduced to selling toys in a station and only just before he died did his work get rediscovered. It would be hubristic to draw even the smallest parallel but it’s a story I can understand. I think it is sad that such an exuberant artist was abandoned and overshadowed; most of us animators owe everything to him. His films are utterly beguiling and charming. They may not deep or profound but their sheer joy of life, their giving of life to inanimate objects as well as the development of all the tricks of substitution and replacement we use in animation are just cause for celebration.

Sometimes he uses basic animation and he certainly does stop a frame and then tinker in the space between the frames which is what we do. I like the idea of teaming him with a contemporary who was also obsessed with illusion. I am obsessed with illusion. There are others I would like to make films about. There’s Verdi, Stephen Sondheim, Hitchcock, Puccini, Chaucer, Keaton, Stephen Foster – well so many. I like understanding how the creative process works. If I am honest, my films may be little more than personal tributes to people and art forms that have inspired and excited me. Maybe, I am just saying thank you a lot! I have people asking whom my great heroes and I think they expect me to say Ray Harryhausen and I do say Ray but I must confess I do not have the dinosaur gene. But Ray is of course a hero, and an outstanding creative individual, and I am most happy to have spent time with him.

Although you have managed to skillfully fit an entire 53 year long lifespan into just 13 minutes is there anything you would liked to have included in the film that you did not have the opportunity to?

What is a little unnerving is that I was 53 when I was asked to do the film. I would have loved a longer film, which would have enabled me to include more of his music. I only hint at his operas. I would have liked to have shown more of his complex relationships and sexuality. And he had some very strange idiosyncratic habits, but these really would have taken a longer film. 13 minutes is a small amount of time, but I think I gave a hint of his character. I did do my research so next time you see it have a look at the way he conducts and holds his baton in a slightly unusual way. Some people have questioned this but that’s how he did it. You have to be quick to see the part were he tears a piece of the manuscript and eats in, which is what he used to do when he got agitated. Also he apparently supported his head with one hand as he conducted – this gets the briefest of references. His truly bizarre and misguided marriage deserves a whole film, although Mr. Ken Russell got there first. So much potential, but what I wanted from the film, more than anything, was for Tchaikovsky to see that, yes, his life had been troubled, but there was Swan Lake. That is some achievement.

Your two new films were both produced outside of the UK. Is it difficult to find funding for such films in the UK?

I fear substantially budgeted short films are basically gone from the UK, but it’s good to see projects such as Canimation. There are several frustrating schemes where you make the film and then if you are lucky, you will get picked up for distribution. There does not seem to be much funding for development. Having said that, with the doom and gloom of Bob the Builder going abroad and Cosgrove Hall getting pulled down and loosing Mark Hall, there does seem to be an exciting Phoenix rising in South Manchester, thanks to Mackinnon and Saunders, among others.

That you can’t elaborate on?

That I can’t elaborate on, no sorry. But Manchester will be the centre of animation again, and I’m happy to be part of it. As a little postscript, though, I went to see the old Cosgrove hall site and I gathered that the builders had no idea of the history of the building. The site is going to be a nursing home, so I am going to write to the company and ask for them to name the rooms “Toad Hall”, “Greendale” and “Cockleshell Bay”.

Well I’m not entirely sure “Toad Hall” would go down well with residents of nursing home!

I’d be happy to end up in Toad Hall! I owe everything to Cosgrove Hall and Mark Hall, I was in Poland a few months, receiving a lifetime achievement award for my work with students and I dedicated it to Mark. When I started I didn’t have any training and the best type of training for anybody is for someone like Mark to say “Right. Welcome, you are going to production now!” To work on quality series “Wind in the Willows” or “Chorlton and the Wheelies” is such good discipline. A tough, relentless schedule, but what an experience. I worry about students nowadays who have had a great time at college and university, on a very relaxed schedule. The reality is very different. “Wind in the Willows” was one of the most enjoyable periods in my life. To be Toad for several years was a gift, not a job!

My ambitions, when I started, was to be an actor and I think, no I know, I would have had very limited success with that, but to be able to play Toad, The Pied Piper of Hamlet, to play Shakespeare, to play Tchaikovsky and to play his piano music, to work with Gilbert and Sullivan, Verdi and the Greek Tragedies, with the odd, very odd, dancing vegetable along the way, is a wider range than most actors would do in their lifetime I believe. I don’t have much cause to grumble, but when I do grumble it is usually about my potential being thwarted or usurped. If I am honest, I had hoped there would have been a feature under my belt by now. I feel, or am frequently made to feel, that short films are a lesser achievement than feature films. Being seen as, or exposed as second rate, and we are back with Tchaikovsky here, is a constant fear. It is tough, I’ll admit, to watch these stop motion features, knowing just how much I could have contributed. Yes, all about potential being realised.

There is a nice story of how you started at Cosgrove Hall by writing to them. Can you tell us that?

I was working in theatre at the time and took the train to Pitlochry, to do a season there. On the way up I was reading the TV Times about an animation company that had been set up in Chorlton, which was where I had been living. I had no idea it was there. So when I got to Scotland I watched Chorlton and the Wheelies and enjoyed it very much but I thought the characters were not really performing. In absolute arrogance I wrote an 8 page letter to Mark Hall telling him I believed I could get some performance from the characters. What I didn’t say was that I had never touched a puppet in my life at that point! Though to be fair, I was in the middle of doing a hugely complex, ridiculously complex cut-out animation of the Twelve Days of Christmas, though I only got to the eleventh day. I understood performance, body language, timing and gestures and in a touch of kismet Mark told me he was in Pitlochry the week after on holiday and offered to meet me. I think the ingenuity and problem solving of Twelve Days made some impression. Mark invited me to an audition (a tough one I might add). Something must have been right as I began working on Chorlton immediately. There was no training. You just had to get it right! Thank you, Mark Hall, thank you.

34 years ago that was, and you know what? I have never been bored in those 34 years. I have been frustrated, angry, disappointed, exhilarated but I have never been bored. Not once.

Timelapse footage of Barry Purves working on the film. By Joe Clarke