ANNECY 2024: The Glassworker – Review

The fact that The Glassworker exists is amazing. Produced by a studio built from the ground up, amassing around 500 employees and storyboarded solely by its director, Usman Riaz, the film is significant for being the first animated feature to come from Pakistan. Its story is grounded in the history of the country too, taking huge inspiration from Studio Ghibli to tell an anti-war tale.

The comparisons to Ghibli don’t stop at its themes. The visuals of The Glassworker are a clear homage to the famous Japanese studio in the way characters look and the homely blue-green colour palette. Also appearing are soft piano-tinged music and a focus on hard work and craft.

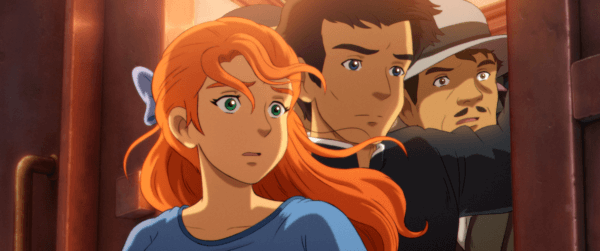

Even with so many direct lines linking the work of Miyazaki to The Glassworker, Riaz’s film creates an original feel and atmosphere due to the passion present in his storytelling. The Glassworker doesn’t have soft, lovely visuals because Ghibli films do, they’re there to represent the innocence of its main characters, father and son Thomas and Vincent who supply a small village with glass-based art and products.

The process of glassblowing is a gorgeous thing to experience in real life, and the majesty of the process is enhanced through The Glassworker’s 2D animation. Seeing such delicate crafts rendered in traditional animation brings parallels between the art depicted and the act of animation itself. Glassmakers create otherworldly pieces of art from raw materials found on the most ordinary of beaches, emptying air from their lungs as a core part of the process. It’s difficult to find another practice that visually represents the idea of pouring yourself into your craft.

We first see the process from Vincent’s perspective as a child where the wonder of hot, malleable glass radiates from the screen. His first involvements in his father’s work lead into an adult Vincent running the place himself, a life dedicated to his craft. But as with anything made with pure intentions, the world finds a way to corrupt it.

War arrives on the shores of this small village in the form of Lord Amano, a military leader who sets up a new base while Vincent is still a boy. Thomas rallies against the once peaceful village now being littered with soldiers, its people becoming radicalised towards the war effort and its school children being sent to the front lines. Pakistan itself was born from a similar story. Soldiers from Britain showing up in a once united territory, sucking the land and its people for as much as humanly possible before partitioning them on religious lines, leaving millions more to die in the ensuing conflicts over territory that continue to this day.

Amano, despite clearly being the film’s antagonist, is painted with a subtle brush. At once he denounces Thomas as a pacifist and forces him to use his glassblowing skills to craft weapons of mass destruction, but he also is able to appreciate the artistry of glassmaking, regularly stopping by to appreciate Thomas and Vincent’s newest creations. Amano instils his love for the arts in his daughter, Alliz, through whom much of the story is framed.

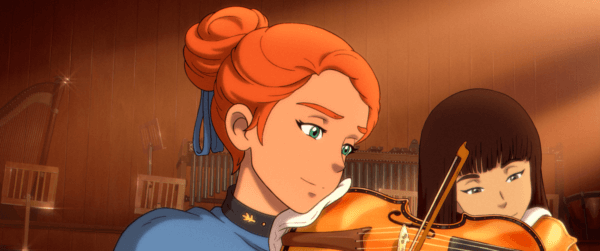

As an adult, Vincent finds a letter from Alliz looking back on when they first met as children and their journeys into adolescence and into love. Their pure connection was formed from a mutual ambition to be artists, each looking at the other in wonder at what they can make from either sand or the strings of a violin. Eventually, war will cause a rift between them too.

Their reverie collapses during an air raid on the village in a scene where the main thesis of the film is brought to the fore but through a measure of narrative immaturity. After sheltering from the raid, Vincent and Alliz find themselves in an argument sparked by Alliz trading letters with Malik, a soldier on the front lines. This ignites a jealous outburst in Vincent which awkwardly contradicts his soft spoken, polite manner up until this point. It feels especially out of place considering the horror they had just witnessed not five seconds ago.

Jealousy consumes Vincent, distorting him into someone completely different. He criticises Alliz for her unoriginality as an artist, claiming that true artistry isn’t mimicking the works of those who came before you but crafting something that’s your own. The attack on Alliz’s identity is unwarranted, but is a way of showing how being labelled as a pacifist coward had been eating at Vincent below the surface, there just could have been a more elegant way of expressing that.

Slowly drifting through the world of The Glassworker is a joy. Its layers are revealed at leisure but builds towards a resonant look at the individual cost of large-scale conflict while delivering on thousands of gorgeously painted frames. The hubs of animation are so concentrated in the far west and far east that we don’t consider the stories to be told and images to be seen from places in between Burbank and Kyoto. The Glassworker might be the first time people have seen Gulab Jamun depicted in 2D animation, or a film that acts as an analogue for Pakistan’s trajectory as a country. The Glassworker is a wonderful film in its own right, but also deserves to be the first of many animated tales from underrepresented nations.