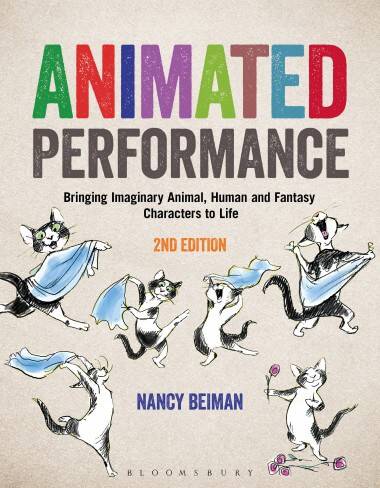

Review – Animated Performance (Second Edition) by Nancy Beiman

The key to this book is a line that appears well over halfway through – “There is no one way to animate anything. Experimentation is the soul of animation.”

Rather than going into great detail about how to animate various types of walk or run – something which, after all, is well enough covered in other texts – Beiman focuses on how to approach animation; how to think about what it is you’re trying to achieve, and then gives you the tools you need to set the ball rolling.

Rather than going into great detail about how to animate various types of walk or run – something which, after all, is well enough covered in other texts – Beiman focuses on how to approach animation; how to think about what it is you’re trying to achieve, and then gives you the tools you need to set the ball rolling.

In the first chapter she covers basic principles. She starts with the classic bouncing ball and pendulum exercises and goes on to explain how these two movements form the basis of all movement in animation. This is followed up with an introduction to the concepts of line of action, silhouettes, anticipation, squash and stretch, although she doesn’t provide exhaustive examples of how to apply these principles: Occasionally perhaps it feels a little too sketchy – for instance the second chapter opens with a rather challenging introduction to creating a walk cycle, then advises you to go on and try some variations, using different lines of action as described in the first chapter, but doesn’t continue with examples of how these might look. Also the instructions for the walk cycle itself are perhaps a little hard to get your head round unless you already have a basic grounding – since chapter one is all about the basics, a clearer introduction to the keys and breakdowns of a walk cycle might not have gone amiss here.

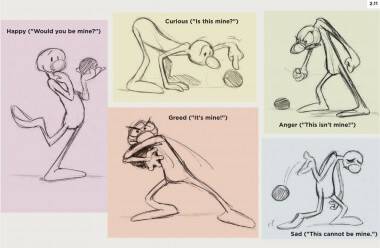

However, it’s easy enough to find that information elsewhere if you need it. Rather than getting deep into the nuts and bolts of animation (that’s what Richard Williams is for) this book is more about the broader approach – not so much the mechanics of putting one foot in front of the other, but of getting a clear idea of who your characters are before you begin animating, so that their thoughts and motivations are clear in your head as you work, and how to give those ideas form. It gives the rationale behind the approach as well as how to do it. You come away with an understanding of what animation is all about, how to approach it and how to think about it, which in turn helps to give an idea of how to apply this understanding to your work.

There’s much emphasis throughout on experimentation and finding your own path rather than leading the way too much, and there are plenty of stimulating exercises to kick you off. This is backed up with lots of input from accomplished industry veterans on how they approach their craft – in particular, Ellen Woodbury (who animated Pegasus in ‘Hercules’) goes into detail on her approach to animal characters.

The book is laid out in an attractive and engaging way, so that it’s a pleasure to dip into as well as to read from front to back. Many useful quotes and snippets of interviews from veterans like Art Babbitt make it an entertaining as well as an educational read. Also it’s full of useful references to live-action as well as animated films, something that’s often overlooked. Keaton and Chaplin are great sources of inspiration (though I’d add that silent films have much to offer the animator beyond comedies).

Sample Pages (click for larger images)

Overall, the book provides what it sets out to – an understanding of the role of acting in animation – and sets you on the path to mastering it. It fills an important gap in many standard texts on animation, while not duplicating too much of what is available elsewhere. If you’re looking for a grounding in animation technique with an inspiring overview of its challenges and potential for creating engaging characters, this is an excellent book to have as part of your toolkit. If you work your way through it with a copy of Richard Williams at your elbow to help you with the details, you can’t go far wrong. On the other hand if you’re already a seasoned animator you’ll probably still to find enough new material here for you to flex your creative muscles in new directions.

Items mentioned in this article: