Animated Encounters 17th International Film Festival – Overview

Anybody who works in film and animation within the town of Bristol seems to have a strong sense of the importance of its annual Encounters International Film Festival, which for nearly twenty years has been one of the UK’s most highly regarded industry events. Originally known as Brief Encounters, it incorporated its sister festival Animated Encounters (which began ten years ago) into a single, all-encompassing event in 2006. Last year the two strands branched off once again, this time occurring simultaneously but at separate venues – Bristol’s Watershed cinema for live-action and across the river at the Arnolfini arts centre for animation. Proving successful, this model was again adopted for the 2011 (and, presumably, beyond) edition, which took place from November 16th-20th. While the strength of the Encounters live-action selection warrants high praise, my focus was predictably on the cartooney side o’things.

“The Backwater Gospel” (Dir. Bo Mathorne)

The Arnolfini has been a preferred venue of mine for a long time, mainly for its art-themed bookshop which attempts to ensnare me with its siren call of “Buy all of us, Ben. We are so very pretty and gigantic and culturey…” every time I pass it on my walk home. As a regular hangout between screenings during the festival it cultivates an appealing atmosphere in which to mill about amongst other filmmakers, teachers, students, directors and independents. All of these were represented in some capacity or other at the festival’s first major panel discussion of the Animation Alliance UK, a newly-formed group of advocates presently striving to keep national independent animation alive despite the onslaught of challenges it is presently facing. While the discussion served to address some major concerns and clear up some misconceptions in regard to applicable tax credits and expectations of work quality in lieu of terrifyingly diminished project budgets, it also shone a light on the fact that any one solution will be extremely difficult to formulate if international assistance is, by definition of the alliance’s terms, not an option. However as a first public meeting it was encouraging and a fitting start to the festival to see that, if we’re in as much trouble as the writing on the wall tells us, at the very least we are supporting one another whilst riding it out. By contrast, UKTI’s “Building Blocks of Preschool Animation” presented an incrementally more hopeful short-term future for the world of broadcast animation, one more dependent on other countries from an economic standpoint. Preschool programming, while just as beholden to budgets, effective pitch work and expectations of marketability as any type of serialised content, seems less firmly placed on the chopping block; Whether this is by virtue of consistent audience appreciation or financial feasibility in general is hard to tell or predict.

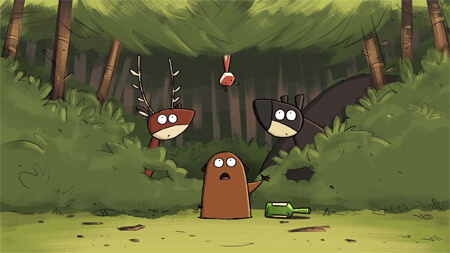

“First Contact” (Dir. James Cunningham)

The focus of the festival was much the same as that of most others, being the competition screenings. The most notable change for the better in this respect was the decision to group films thematically, with six main categories: “Animated Worlds”, exploring the created environments and backdrops as a pivotal component of storytelling; “Animalis Anima”, showing that anthropomorphism in cartoons will never die; “The Human Condition”, a selection of the more philosophically analogous, life/universe/everything-type films; “Near and Far”, films bound by the theme of travel; “Domestic Bliss”, focusing on family and relationships; and finally “Light and Dark”, juxtaposing some of the less immediately accessible elements of animation against the most conventional, occasionally within the same film. By and large the quality of the selection was consistently high, with “Near and Far” the only presentation lacking somewhat in diversity but bookended by two of the stronger pieces, Grant Orchard’s “A Morning Stroll” and Bianca Ansems’s beautifully constructed NFTS short “Playing Ghost”.

“La Detente” (Dir. Bertrand Bey and Pierre Ducos)

The biggest crowd pleasers in general tended to be either the visually inventive (such as Juan Pablo Zaramella’s “Luminaris”, combining the warmth of old Méliès films with modern-day pixilation; Christopher and Christine Kezelos’s stop-motion ode to classical music “The Maker”; Daniel Seideneder’s astonishingly-detailed, time-lapse-in-miniature piece “Hurdy Gurdy”; and Darcy Prendergrast’s highly laudable collaboration with All India Radio “Rippled”, realised by a combination of long-exposure photography and light painting) or just plain funny (Phillip Warner’s “The Cameraman”, vignettes of a CCTV operator’s workday with a nice sprinkling of darkness toward the end; Sam Morrison’s tale of birthday card-inspired introspection “Greetings”; Jadwiga Kowalska’s wel-timed, textural cutout piece “La Fille et Le Chasseur”; Tomer Eshed’s suitably flamboyant “Flamingo Pride”; James Cunningham’s hilarious CG/mocap intergalactic peer review “First Contact”; Louis Hudson’s scatological rom-com “All Consuming Love (Man In A Cat)”; and the macabre “Chroniques de la Poisse” by Osman Cerfon, exploring the lighter side of violent death) a quality of animation anyone should be able to get behind, and one the festival audiences were certainly receptive to. Other films were hugely satisfying for their sense of grandiose spectacle, such as the hallucinatory, candy-coloured war deconstruction “La Détente” (Bertrand Bey and Pierre Ducos) and Nobrain’s “The Gloaming”, a mixed-media epic detailing the rise and self-destruction of society (with some willy gags thrown in for good measure).

“Damned” (Dir. Richard Phelan)

Some of the most encouraging work came in the form of recent graduation films, with the high-concept “Slow Derek” (Dan Ojari) and the visceral “Belly” (Julia Pott) in keeping with the consistency of the RCA’s stronger output. Other represented institutions were the Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg with the guardian-angel-in-peril short “Angelinho” (Maryna Shchipak), the Bristol School of Animation with the beautifully designed “Liberties” (Beatrice Borghini), the NIAF with “Zaliger” (Nina Gantz) and the Animation Workshop with “Last Fall” (Andreas Thomsen) and “The Backwater Gospel” (Bo Mathorne), both making uniquely inventive use of CG combined with traditional line art aesthetics. The greater output of well-crafted student work came from the NFTS, which included “Damned” (Richard Phelan) and “Bertie Crisp” (Francesca Adams), two traditionally-animated tales of animal misadventure, warmhearted and blackhearted respectively, though both fabulously crafted and witty, as well as “Kahānikār” (Nandita Jain) and the aforementioned “Playing Ghost”, which nicely explored the importance of family and childhood fantasy.

“L.E.R. (R.S.I)” (Dir. João Angelini)

Alongside the competition screenings were a number of retrospectives and showcases, including “Shelley’s Eye Candy”, a collection of noteworthy up-and-comers of the international animation scene hand-picked by Dreamworks’ talent scout Shelley Page on Wednesday, Philip Hunt’s presentation of the body of work Studio AKA is so renowned for on Thursday, and Tomm Moore’s retrospective of Cartoon Saloon, one of Ireland’s most accoladed and prolific studios on Friday. As an appropriate companion screening, a showcase of Irish animation followed, featuring some of the nation’s standout new and established filmmakers such as David o’Reilly, Richard Kelly, Patrick Semple and Matthew Darragh to name a few. Saturday’s spotlight on Brazilian animation (presented by Anima Mundi festival director Léa Zagury) was plagued by sweltering heat, a glitch of the Arnolfini’s faulty AC that, if nothing else, was thematically appropriate. What by and large separates any kind of retrospective screening from a panorama or competition is the switch an audience needs to make in their head from being entertained to being culturally appreciative. As tricky as this can be to do so under normal circumstances, it’s borderline impossible when the entire room is simultaneously fidgeting in sweltering discomfort. That being said, certain films still managed to stick out and paint an enlightening picture of the unique qualities the nation has brought to the table as far as this industry goes, whether visually ambitious (Leonardo Cadaval’s “Pajerama”), simplistically effective (João Angelini’s “L.E.R.”) or gloriously mindless (Marcelo Ribeiro’s “Qualquer Nota”). Another nod should go to Fernando Miller’s “Furico & Fiofó”, which despite being overlong served as a well-observed South American cultural satire in the old school rubberhouse style of early North American animation.

Festival program signed by Mr. K – best souvenir ever

The greatest draw – pun less intended than inevitable – of the festival was not so much a specific event than the general presence of Canadian animation legend John Kricfalusi. From the chatter amongst fellow festivalgoers he was clearly the main attraction to out-of-towners who had made the trek from near and far to see him, and with good reason. Beginning on Thursday, his afternoon retrospective of work spanning the 80s and 90s hammered home just how significant and influential the mark he’s made has truly been, with the inclusion of his skewed contemporisations of once-vanilla properties such as “Mighty Mouse” and “Yogi Bear”, music videos and the unique treat of some classic unedited “Ren & Stimpy” episodes on the big screen. It was perhaps most fascinating to see an example of his oftentimes-maligned revival of the latter (known alternately as “Adult Party Cartoon” or “The Lost Episodes”) get probably the strongest positive reaction of the lot; It frankly warms my heart to see so many peers and contemporaries alike come together to laugh in hearty unison at a wirehanger-abortion gag. It also put paid to a personal theory that broadcast television had never been the forum Ren & Stimpy’s second, ‘adult’, incarnation ever really belonged to – context and environment is a crucial component of appreciation, and the enthusiasm of the crowd was just the right level of manic effervescence to appreciate what he had set out to achieve.

The retrospective was followed up later in the day by an onstage Q&A session conducted by Chris Shepherd (of “Dad’s Dead”notoriety). While fascinating and undoubtedly the most attended presentation of the week, Murphy’s law made sure to come into play and plague the technical side of things with pretty much every conceivable codec and software conflict known to man. Fortunately Kricfalusi’s propensity for chatter and anecdotes was a welcome indulgence and distraction from these glitches. Once the greater percentage of the issues were ironed out, the range of clips, shorts and examples of visual inventiveness went a long way to explaining his most significant influences as a visual creative, as well as the origins of certain character personalities. It was also refreshing to see an animator cite how valuable live-action performance can be as an informing factor (a great deal of the manic, unsettling undercurrents of his work owe a debt to Peter Lorre, Kirk Douglas and Robert Mitchum).

“Close But No Cigar” – ‘Weird Al’ Yankovic (Dir. John Kricfalusi)

What was most revealing and – I’m a little hesitant to admit – surprising was his authenticity and humility when providing his take on the growth of animation and the role he made for himself in trying to get it back on track. He comes across as a man who’s passionate about what he believes and wants others to feel that same passion, a trait possibly misconstrued as a ‘my way or the highway’ type online persona. A true treat for fans was the opportunity to be immortalised in John K style – an opportunity that, being relatively impromptu and incredibly high in demand, saw a handful of people miss out – though most inspiring was glimpsing him around the festival venues perpetually surrounded by a harem of youthful, adoring fangirls.

The Saturday evening awards ceremony covered both strands of the festival, the animated winners being Michael Zachary Huber’s “World’s Apart” (Children’s Animation Jury Award), Michelle Arbon’s “Above As Below”(DepicT! ’11 British Special Mention Award), Bo Mathorne’s “Backwater Gospel” (UWE European New Talent Award), Naomi Zahl and Matt Morris’s “On The Bus” (Best of South West), Grant Orchard’s “A Morning Stroll” (Best of British) with Dan Ojari’s “Slow Derek” earning the Cartoon d’Or nomination and winning the animated Grand Prix. The atmosphere throughout the festival and at the closing party was convivial and, though tinged with concern at the state of things to come, largely inspired and enthusiastic. The one thing that truly needs to be held onto during these troubled times, if you’ll pardon the clichéd turn of phrase, is the energy to keep on creating despite the odds and celebrate why what we do as animators is important. These types of events contribute enormously to that, and it’s to the Encounters Festival (as well as its main team of Liz Harkman, Mark Cosgrove, Kieran Argo, Rich Warren and Mireia O’Prey)’s credit that it too has carried on.

“Slow Derek” (Dir. Dan Ojari) – Winner, Grand Prix