Interview with Anete Melece (‘Analysis Paralysis’/’The Kiosk’)

Back in 2013 Latvian-born animator Anete Melece‘s multi-award-winning short film The Kiosk charmed its way onto the animation circuit with the warmth of its story (in which shopkeeper Olga finds herself trapped in her kiosk while embarking on an unexpected journey) and quirkiness of its humour, amassing international screenings and prizes from Fantoche, Bornshorts and Animateka among many others. Her follow-up film Analysis Paralysis, having already won major awards at Fantoche and the UK’s Encounters Short Film and Animation Festival, is set to follow suit. In this latest short we see two stories intertwine, the first of Anton, a solitary man with only his dachshund for company, plagued by a constant impulse to over-analyse his surroundings, interactions and decisions; meanwhile, a gardener in the park Anton frequents finds herself increasingly frustrated with vandals trampling her flowerbeds…

In anticipation of screening Analysis Paralysis at the Manchester Animation Festival Skwigly spoke with Anete to find out more about her unique process.

To begin with, can you talk a bit about your studies and how these shaped your process as a visual storyteller?

I studied Visual Communication at the Art Academy of Latvia, which was like a big playground where we could try out all kind of media including some basics in animation, but at the core of the studies was learning to think in a conceptual way. So it didn’t matter if one would make video art, installations or photography – most important was the idea behind it and ability to substantiate it. This definitely left an impact on the way I work.

Later I did a Master’s degree at the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts in Switzerland and The Kiosk was my graduation work. There we learned about dramaturgy and other things more related to animation and film making, however I still lacked some technical knowledge, so I was simply learning by doing.

Was animation an area you’d always been keen to explore or did it grow from your illustration work later on?

It grew from my illustration work and comics. After some experimenting with animation and discovering that excitement of seeing your drawings being “alive”, there was no way back.

Your preceding film The Kiosk went on to perform spectacularly well. What was it about the film do you feel that had such an impact on festivals and audiences?

The storyline is quite simple and filled with humorous details. However I guess the main reason could be the charm of the warmhearted main character – the kiosk lady Olga.

Where did the idea for The Kiosk‘s premise originate from?

From my own experience. Around the time when I had the idea I had a decent job in an office and everything was kind of okay, except that I had a feeling that I was stuck and was not growing anymore. When I came to this idea about a woman who is literally stuck at her work-place and is dreaming of freedom, at first I didn’t realise that it was about me. Only when I finally left the job and started to study so that I could do this film did it occur to me, even though it was so obvious.

Unless I’m mistaken The Kiosk seems to be the first major project to embrace digital processes when it comes to your cutout style (preceding films look to be made with analogue processes). Was this an easy transition to make?

I only had to learn a new software, but I was working with an animator Stefan Holaus and most of the animation was done by him so it was not hard at all. The biggest change was to learn to work in a team.

How does the production for a film such as The Kiosk or Analysis Paralysis break down?

After the storyboard is finished I create characters, which usually need to be drawn from five different angles, but it depends how – and how often – they appear in the film. For The Kiosk I used acrylic paints and a pencil, but Analysis Paralysis was done using felt-tip-pens.

Then I scan them and cut all the details in Photoshop. When that’s done, one can rig the characters and they are ready for the animation. At this point Stefan already starts to work on the animatic. For The Kiosk I made animatic out of the storyboard, but for Analysis Paralysis we decided to do it with the finished characters, which could be used later as a basis for the final animation. All the rigging and animation is done in the CelAction. Meanwhile I start to work on the backgrounds – as with the characters, I draw them by hand. When they are finished, Stefan adds them to the animation.

Analysis Paralysis also has sequences drawn frame by frame. These I did first in Toon Boom Studio and then redrew them over the monitor with felt-tip-pens.

When the animatic is ready, we do the voice recordings so that animation can be adjusted to the voices.

At this point, when the timing is more or less set also the composer (Ephrem Lüchinger) starts to make the first sketches for the music. Slowly, slowly everything comes together and I start to believe that some day we are going to finish it.

Are these films produced independently or do you work with studios/funding bodies to get them made?

I work with a producer Saskia von Virág and together we try to get all the necessary financial support from different foundations in Switzerland and also Latvia. Both films had been co-produced by Swiss National television, but The Kiosk was also co-produced by Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts.

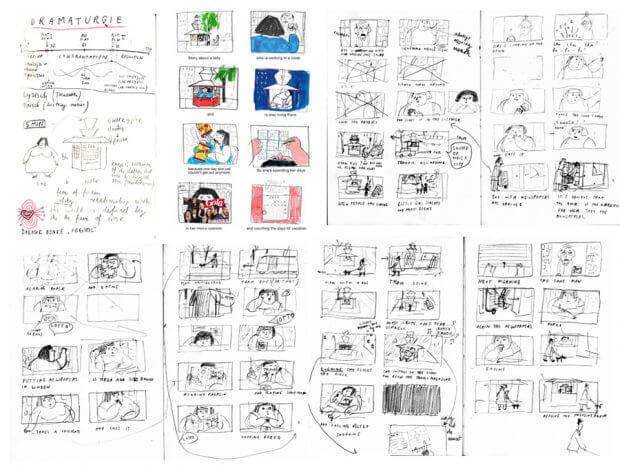

The Kiosk thumbnail boards (via anetemelece.lv)

Analysis Paralysis tackles a potentially heavy-handed subject in a very endearing and amiable way. Why did this topic appeal to you as a storyteller?

I never pick a topic and then develop an idea. Usually I have an idea for a character and only then I think what it is for a topic and while I think about it, I develop the storyline. It is during this process when I discover how the topic is actually related with my own life. Of course it’s not a direct reflection of it, but the are elements that work like metaphors. Similarly to Anton, the main character of Analysis Paralysis, I am often indecisive. So while working on this film I tried to understand the nature of this problem and how it is related to some fears. And one of my fears is to become someone like that gardener – the other character of the film. If I will tell more, I will probably reveal too much of the story so I should stop now.

Given that the visuals take the lead as far as progressing the story, when it comes to the writing itself do you find it to be a more visual process or do you write them as traditional scripts?

I usually “write” by drawing thumbnails, but sometimes my thoughts are too quick and then I have to write some notes as well. But basically storyboard is my script.

Do you often travel with your film to festivals, and if so has that yielded any interesting or beneficial experiences/interactions?

I go to as many festivals as I can find time to. I enjoy it a lot because that is the payoff for the two years of work. Then it doesn’t feel that I have put two years of my life in only 9 minutes, but 9 minutes that I can show two years long.

But of course it’s not about seeing my own film again and again (I have seen it enough), it’s about hearing and sensing the audience while they are watching. To hear them laughing is among the best feedback that there can be. And of course it’s about seeing other films and meeting directors and making new friends. Suddenly you know people from all around the world and it starts to feel like a friendly place to live.

Analysis Paralysis © 2016 VIRAGE FILM

Although you hail from Latvia you’re presently based in Switzerland. Have you found this country to be a better fit for your creative work (and, if so, for what reasons)?

It was not my intention to go to Switzerland in order make animated films there. It somehow happened like this, but it turned out that Switzerland is really a good country for filmmakers as it is possible there to make living only from that. I find it to be a luxury that one won’t find in many other countries. Meanwhile I am currently an assistant director for a feature animation project in Latvia, so I try to keep ties with both countries and fulfill myself creatively there also.

As well as illustration and films you’ve also done several comics. From a storytelling point of view do you find your approach differs from when making films or is it largely the same?

I am rather careless when I choose a topic for a short comic, since I know that it might take a week or month to finish one. It could be simply a joke. As animation is a long process taking much effort and patience, I feel a need to deal with themes that I find deeper and more personal. Otherwise I would probably lose the interest before the film would be even finished.

However my first film was created in a very careless manner and I should probably return to this kind of approach.

Do you have any plans to adapt any of your comics to animation (or vice versa)?

I have thought of turning one of my comics into animation, but I don’t think I will. However there is an idea of making a picture book out of The Kiosk, let’s see if it will work out.

What do you have planned next?

Collect new experiences and impressions and hope one day they will turn into a new idea. I am quite slow with creating ideas for films, but I’m okay with that. It was not the case after my previous film though, that’s why it resulted in a film where the main character thinks too much. So I guess I will continue from the place where I left Anton at the end of the story – that careless approach.

Analysis Paralysis screens today at the Manchester Animation Festival as part of our Skwigly Screening at 3:15pm in the HOME event space. Other upcoming screenings include the 32nd Interfilm International Short Film Festival, Animated Dreams, Anilogue International Animation Festival and Animateka International Animated Film Festival.

To see more work from Anete Melece visit anetemelece.lv