Annecy 2022: A Conversation with Amanda Forbis & Wendy Tilby (‘The Flying Sailor’)

Today on Skwigly we’re excited to present an exclusive chat with acclaimed Canadian filmmakers Amanda Forbis and Wendy Tilby. The filmmaking duo first paired up to create the highly-accoladed 1999 short film When the Day Breaks with the National Film Board of Canada. Picking up major awards at Annecy, Animafest Zagreb and the Hiroshima International Animation Festival the film, which tells the story of an anthropomorphic pig and her emotional response to witnessing an accidental death, would also be nominated for an Academy Award® (a second for Wendy, whose solo, paint-on-glass NFB film Strings had been similarly well-received). Having worked together ever since, Amanda and Wendy have since produced commercial work for clients including Suntory Water, United Airlines, General Motors and Ohio Health among others, as well as a follow-up 2011 NFB short film Wild Life in which a young remittance man moves to the US in a shambolic attempt to try his hand at ranching; as with its predecessor, the film would go on to be nominated for an Academy Award®.

Having continued to produce commissioned work for a variety of clients and outlets as well as receiving the 2018 Winsor McCay Award for Exceptional Contribution to the Art of Animation in the interim, Amanda and Wendy have this year completed their third NFB short The Flying Sailor. Based on the tragic Halifax explosion of 1917 that killed thousands (notably the surreal story of one particular survivor who was propelled in the blast and landed, naked, over a kilometer away), the film marks several advances in the duo’s mixed-media approached to filmmaking, specifically the integration of CG elements in a manner that perfectly complements their established, painterly approach to character design and environments. With The Flying Sailor screening as part of the Annecy festival’s official selection this week, Skwigly were enthusiastic to meet Amanda and Wendy to discuss their incredible work and unique creative processes.

I gather you both met at university, is that right?

Amanda Forbis: Yeah, it was a college then and is now a university – the Emily Carr University of Art and Design.

Wendy Tilby: Yeah, we both landed at art school, having been at university before that. I think we both went there more interested in live-action filmmaking and fell into animation while there, so it was a little bit of a haphazard thing.

AF: When we met, Wendy was in her fourth year doing her graduation film, Tables of Content, and I was in second year, live-action with a little side gig in animation. That’s how we met and became friends.

WT: But we were both attracted to animation, probably for the same reasons of avoiding live-action – the standing around, the hierarchical nature of it, the dilution of the creative process. With animation being kind of solitary, you get to control everything, which was more appealing, and we both had an art background. So it kind of came naturally, to get into animation, so it happened that my graduation film was animated. And so was yours, I guess?

AF: One of them, yeah. As Wendy says, just that dilution in live-action, where you go out on set and there’s all that standing around, then these concentrated moments where you’re getting the shot. Whereas this way, you’re sort of always engaged with the shot in animation. You’d just be more likely to get what you wanted, it seemed to seem to me. I realize how naive that was now, because it’s so much work, but that’s what it seemed like then!

Amanda Forbis (L) & Wendy Tilby (R) (Image courtesy of the NFB)

You mentioned the solitary aspect there, and of course you’ve been making films together. Initially were you making your own projects to begin with?

WT: Well, art school, because we were in different years, we weren’t working together, although Amanda helped on my student film…

AF: A little bit.

WT: …at the end there, but it wasn’t until a few years later that we actually got together to make When the Day Breaks in Montreal. So we each had made our own films. I had made Strings at the Film Board in Montreal and Amanda had worked on a project in Vancouver.

AF: Wendy’s film was paint-on-glass and I was doing animation direction for educational film at the NFB in Vancouver, it was a cut-out film. I had a crew to make the cutouts but it was the same as Wendy, where you’re just very isolated, just you and the camera. So When the Day Breaks was our first collaboration and we’ve collaborated ever since.

And that was also NFB, did that project come along from having worked with them previously?

WT: Yeah, I was in Montreal, Amanda was in Vancouver at that time. A while after I had made Strings I was sort of mucking around, trying to figure out what my next project would be, and it eventually evolved into When the Day Breaks. I was quite sure I didn’t want to work under the camera again; the story was clear to me but how to execute it went through a lot of trial and error. Amanda was finishing up her project and, because we were so simpatico in our sensibilities and our senses of humor, she came to Montreal and it sort of evolved from there. We developed the technique that we ultimately used, which was a relief for both of us, to not be working under the camera. Even though the solitary aspect of it is still very appealing, it’s hard to collaborate working under the camera, so this was a way that we could both work on it. If you’ve seen When the Day Breaks, we use video but each each frame is hand-painted, which is appealing to both of us because we like doing that.

AF: When I think about under the camera work, I feel really nostalgic about it, but maybe in the same way that I feel nostalgic about Steinbecks and cutting celluloid; if asked “Do you want to go back?” I think I’d say “No”.

WT: Yeah, it’s hard to go back from what the digital world has brought us in terms of flexibility, but we also acknowledge that it’s a bottomless pit of possibility and, as I’m sure you know, one thing about working under the camera is that it keeps you in check. You have to keep moving forward whether mistakes are made or not, and the mistakes have to be pretty bad for you to do it all over again. With the computer it’s like you can endlessly fix things, so it’s a double-edged sword, I would say

I’d love to kind of get into that technical side of things a bit more with When the Day Breaks, because it is a really interesting end result, that sense of movement. When you say video, then, is it essentially a type of rotoscoping?

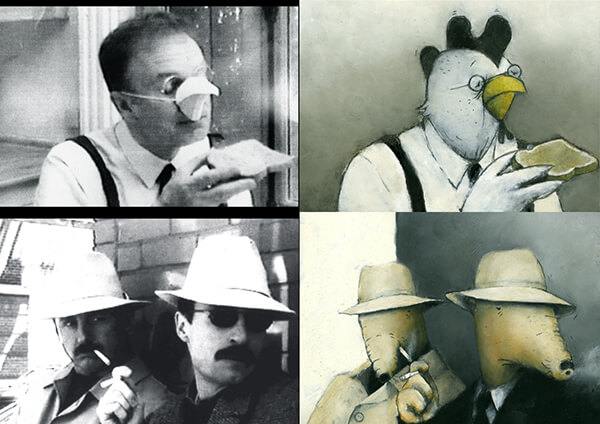

AF: What we did, just to go from beginning to end, was we would shoot live-action on a home video recorder and we might add a beak or something you know, so we each acted out the chicken and the pig and we’d go out on the street and cross the street that kind of thing…

WT: Totally embarrass ourselves!

AF: They were terrible looking props, they looked like they’d been made by a six-year-old (laughs) and then we’d bring it back in. At the time, frame-by-frame on video was almost impossible, except on these really expensive, fancy, three-quarter inch decks. So we transferred to the three-quarter deck and then you could scroll through the frames, frame-by-frame, without the scan lines and all that kind of stuff. From there we would print out select frames to a video printer, which was a box with thermal paper in it.

WT: Usually used in medicine for ultrasounds, medical imaging, that sort of thing.

AF: So it produced a black and white image and had a fairly good grayscale on it. From there we would number and photocopy those selected frames.

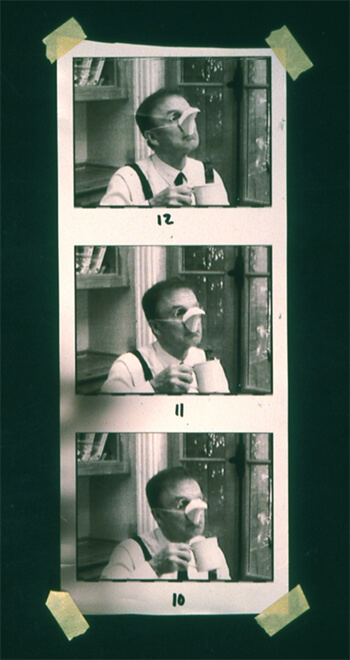

WT: And they would come out in strips, almost like film strips but strips of video.

When the Day Breaks frame printouts (image courtesy of Amanda Forbis & Wendy Tilby)

AF: So then we would draw on those, paint on them, kind of estimating the positions of the characters – because the body movements would be roughly what was laid out, but the head shape and movement of the head we always had to kind of estimate as we went through the shots, by eye. Then we’d shoot them under the rostrum camera.

WT: Then other parts of the film did not use video at all, sometimes they used still images, or drawings, it was only the character stuff that was used with this video. It was kind of fun because you had something to draw on top of, so let’s say this chicken is on the street, we would draw in all of the elements that we wanted to add, like a beak and the hat and everything, and we would paint out what we didn’t want. It was free form, in a way, it was very loose in a satisfying way.

AF: Except for those occasions when we were desperately trying to paint out something we didn’t want from the background. Because there were often times when we had not shot under absolutely ideal circumstances, so we’d put layers and layers of paint on it but never quite obscure it. That was really frustrating. We were very careful not to rotoscope in the classic understanding of the word, because rotoscoping often looks ‘soupy’, there’s no crispness to it, usually it feels very lax. And so we sped things up and put in holds. With the subway shot, we actually took the train coming in and then just repeated it going out again, just flipped the shot, so we pulled all kinds of little tricks to make the movement a little more interesting.

WT: We always described it as almost like reverse pixilation; if you were doing a pixilated film, you would take a camera and shoot somebody, and you would just take certain frames with your camera – we would just do that but after the fact, after it was shot, by a process of selection.

When the Day Breaks footage-to-final-film comparison (image courtesy of Amanda Forbis & Wendy Tilby)

Back when you were shooting it, would you have been able to look back at an hour or a day’s worth of work and see how things were going? Or did you have to wait for things to be sent off and processed?

AF: That would have been ghastly! We had a video testing system where we could check things out along the way.

WT: Once everything was painted we would shoot it on film, under a rostrum camera – it would be several days before we saw that, it would be processed at the Film Board, which had a lab at that time. But yeah, we were testing in advance of that but we wouldn’t really see the full effect until it came back from the lab.

Of course, when it was done, it was an enormously well-received film, and I imagine generated quite a lot of exposure. What effect, would you say, did that have on what you ended up doing next?

WT: One thing it did, which is kind of interesting when you talk about technique, was it generated some interest within the advertising world, which we have one foot in as well, we’ve done quite a few ads. But what was interesting was that, not long after finishing When the Day Breaks, we did a campaign with United Airlines where they said – and they weren’t the first to say this – “We want the When the Day Breaks technique!”, and we would go “Oh God.” (laughs). It’s an insight into how the world of advertising is always pillaging from the art world, so we were asked to pillage our own work in that way. But the funny thing was, in describing our technique, as we just did to you, the key part of it was that we were turning humans into animals; that’s what made this sort of quasi-rotoscope technique work, for us, it made it interesting. If you were just turning them into another kind of human, it was not as interesting. But United Airlines wanted humans in this technique. We really didn’t want to do the human thing but we ended up doing it. I don’t know if you might have seen it, but it’s a little bit gruesome! So it did spawn a few other ads with United Airlines.

AF: They were great gigs. It was the sweet, happy days of advertising, where they paid you and fed you and fussed over you, it was fabulous.

WT: We did another one for Earthlink, which was also in that technique. Also with the Film Board, it certainly enabled us to make our next film, which was Wild Life. So you know, having a successful film certainly gives one opportunities.

AF: I think, in terms of how it affected the creation of Wild Life, other than creating that opportunity, was that we decided to use language. The burden of language-less storytelling is considerable, to get your ideas across, so we quite enjoyed that.

WT: We also wanted a change.

AF: But we really enjoyed using language, writing dialogue, having the characters speak, working with actors and doing the lip sync. That was really fun, actually. One thing that carried over from When the Day Breaks into Wild Life is the use of real media, because Wild Life, at least in our minds, was kind of this tipping point between analogue and digital rendering. We struggled so hard to find something that we would be happy to do in the computer and it just wasn’t there. The brushes weren’t there, our abilities weren’t there, so we retreated back to real media.

WT: We animated digitally for Wild Life but ended up hand-painting it all in gouache on paper.

So was it scanned in, then?

WT: Yeah, we would animate in Flash and then print out all of the images with registration marks, paint everything, and then scan it all back in, which was kind of crazy. We wouldn’t do that now, just because it makes no sense and the digital tools are so much better now. But even now you can’t replicate the real paint.

AF: It just occurred to me too, that there’s this other incredible advantage. When we were working on When the Day Breaks, we would get a whole bunch of the work prepared and then we would go out to our friend’s country place and stay there for a week and just paint in the country, just us and paintings. No computers to be seen. Now, even though we have much more creative freedom, we’re tied to these two-screen, giant computers. You don’t want to haul them all over the place when you’re on holidays. So that’s a big trade off.

Also with the shift from the previous film, Wild Life is ostensibly more of a comedic film, before it takes a turn towards the end, but there’s all this wonderful character business with the endearingly hopeless guy in this endeavor that’s sort of doomed from the outset. Had that been something you wanted to do more of, something a more explicitly comedic?

AF: Yeah, I think so. I mean, the subject matter really lent itself to that, because the history of those remittance men, as they were known, is really funny, and then it has this tragic end where most of them went off to the First World War and never came back. They just brought this incredible color to this very dire, hard landscape, full of people who are just white-knuckling it up on the prairies, and they come and they play polo and they fart around and write to their fathers for more money. It’s inherently quite funny

WT: It’s not even conscious, but we naturally seem to want to mix tragedy and comedy.

AF: It’s more intentional now.

WT: Yeah, When the Day Breaks, even though you could call it tragic, it has a blend, it’s not super dark. Same with The Flying Sailor, it’s just naturally what comes out of us. It’s hard for us to do something completely without humor.

AF: Why bother?

WT: But I wouldn’t describe the films as ‘light’, either.

AF: We just hope to hit that sweet spot of making him a ridiculous character, but also sympathetic, that you’d like him even though he was ridiculous. We didn’t want to have you write him off as an upper class twit and feel nothing for him, then then the film’s kind of lost. So that was a delicate little balance.

When it comes to The Flying Sailor, there’s a note that comes on screen that it’s based on a true story. Was this actually something that happened, more or less how it plays out in the film?

WT: Well, we don’t know how the real story happened (laughs) which is sort of the point of our film, to kind of fill in the gap and make up the trip, but the the premise is true. At the end we dedicated it to this story of a sailor named Charlie Mayers, all we know about him is just one paragraph that’s been written about him, because he’s just one of many people in that terrible event. But the Halifax explosion, that really happened – two ships collided in the harbour in 1917 and one of them was loaded with explosives.

AF: That’s pretty accurate, it’s exactly as ridiculous as it happened in our film.

WT: And it was a total freak accident, one was in the wrong lane. We could have milked that whole scene a lot more but we wanted to get to the real meat of the movie for us, which is the flight. But a sailor was there on the docks and he was in the blast and he landed, naked, two kilometers from where he started – and lived and ended up going back to Manchester! So we were at a museum in Halifax many years ago, and the whole exhibit was dedicated to the explosion, which absolutely devastated the city. Horrible, horrible stories. I mean, it was the it was the biggest manmade blast before the atomic bomb. The stories are incredible.

AF: It killed 2000 people instantly and then many more after that, which they didn’t properly record, so the actual toll is not really known.

The Flying Sailor (Dir. Amanda Forbis/Wendy Tilby, ©2022 National Film Board of Canada)

WT: It’s remarkable that he avoided getting killed, but he landed kind of uphill, in a park! That probably is what saved him. When we saw this little write-up about him we were intrigued, like “What would that have been like?” Near-death experiences are really quite fascinating in how much they all have in common, you know, about time slowing down and the senses sharpening, white light, a review of your life, a sense of peace and calm and bliss at the end, a dilemma whether to go back to your body or to die, those things are quite universal, in a way. So we wanted to capture those things, but were intrigued by combining the horror of his situation with the beauty of his flight. We thought of it almost like a ballet, that he would be up there, he would rise above the this mayhem and rise towards a kind of calm and bliss. It was just sort of so beautiful to think of this pink, naked sailor up there, amongst all this debris. And just the idea of slowing that down, we found it funny and quite moving at the same time, just as a notion. And then there’s the violence of his return to earth, and people near-death do often report a feeling of being yanked back into their bodies. And it’s definitely the less attractive choice at that moment, because they’re so peaceful and blissful and pain free, so going back to life is actually much harder than death. And he’s going

AF: And he’s going back into hell, basically; it’s hellish, what he wakes up in.

WT: That post-explosion horror, but he’s alive, so is that a happy ending? I don’t know.

AF: The actual guy, his statement said that he didn’t remember anything of the trip, but that when he woke up he was next to a baby, for one thing, who was also alive, and he was all wet, so that was his memory of the trip. He also was in his 20s, he was just a young guy. We turned him into middle-aged guy, ’cause that’s how we roll these days (laughs).

The Flying Sailor (Dir. Amanda Forbis/Wendy Tilby, ©2022 National Film Board of Canada)

The character design does kind of bring to mind some of the character work in Wildlife but overall it’s a very distinct film in its visual approach, looking back at the other two. Its own mixed-media approaches, I feel, are kind of unique to this, like with the boats and some of the post-effects and flashbacks all interwoven. Does the film represent you embracing the digital side of things a bit more?

AF: Yeah – well, for one thing, it just was not feasible for us to blow down a city in 2D animation, that just wasn’t gonna happen!

WT: And we really wanted to show the city from his point of view, that was important. If we were to draw that by hand, with all the perspective changes, it would have been beyond us. I mean, it was extremely hard to do it the way we we did it, too.

AF: Yeah, the 3D aesthetic has been historically such a dodgy proposition, where it’s only really now kind of showing its potential. We knew that with our limited experience with it, and that we’d only have a small crew available to us with our budget, we knew that it had to be simple, it couldn’t be super sophisticated. So we purposely went for what we hoped was kind of a model-train aesthetic, so that things hopefully look like they’re carved out of wood or something.

WT: So we enlisted a guy to work with us who knows Maya, William Dyer, he sculpted all these houses and buildings. It actually pains us that in the end, because of the perspective and that we ended up blurring things more, and they’re a little bit more distant, we don’t actually see the buildings the way we wish you could, because some of them are really cute and really great-looking. We kind of designed all the buildings, but he would make the shapes and we did the skins which would be painted digitally in Photoshop. And they really did look like they were made out of little wood blocks. That was really fun. So everything got arranged, telephone poles and the boats and everything like that. But our main fear all the way through was that it was going to look horrible in a digital way, and it wasn’t until quite late in the process that we started to feel like we got it. It was such a strange way to work, but yet kind of amazing. So it was really good for us to enter into that world and see how it works.

AF: But the sailor we always wanted to be kind of roughened up, especially when he’s in the air, the way he just boils like crazy, his edges are very loose. That was always important to us, that he had this kind of roughness, it felt important that he be separated so he’s clearly the subject from beginning to end. I think that that’s part of why we did it. That again, would have been very difficult to animate in 2D, because he’s moving so slowly and the changes of his position in the air are so pronounced. So we we did end up animating him in Blender, we did that ourselves, and then painted over the top of that in Photoshop, to give him more of a looser feel, a more disrupted feel.

The Flying Sailor (Dir. Amanda Forbis/Wendy Tilby, ©2022 National Film Board of Canada)

Are you excited for it screening at Annecy?

WT: Yes, very. I mean, we have yet to see it with a big audience. We’ve only seen it with a handful of people.

AF: It’s really different on a big screen, that’s for sure. We produced it here in Calgary and then we went to Montreal to do all the post production. The first time we saw it on the big screen we were like “Oh, my God!” – you know, some of the sort of vertiginous effects that you want, like when you’re dropping down to earth, all the time when we were in production we were thinking “This doesn’t really do anything”. And then we get in there and you think “Oh, that makes me feel slightly unwell!”

WT: Yeah, and sound was a huge part of our process. It was really important, as it is in all of our films, but the music was so important to us in getting the right feeling and having it work with the sound. The mix was a really interesting process, we worked with Luigi Allemano who did the sound effects and the music and it was really fun.

Annecy festivalgoers can catch The Flying Sailor as part of the Official 3 programme.