Q&A with ‘Turbine’ director Alex Boya

With a distinctive design style and penchant for the simultaneously engaging and bizarre, Bulgarian-born, Montreal-based animator Alex Boya leanings toward animation developed while studying at Concordia University’s Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema, building on his lifelong enthusiasm for drawing from observation. Alex has recently directed Turbine, his second film with the National Film Board of Canada.

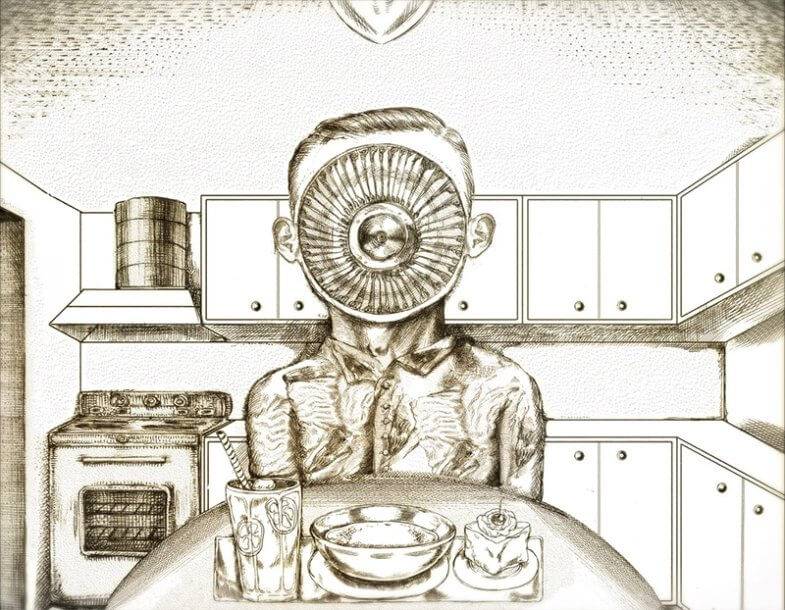

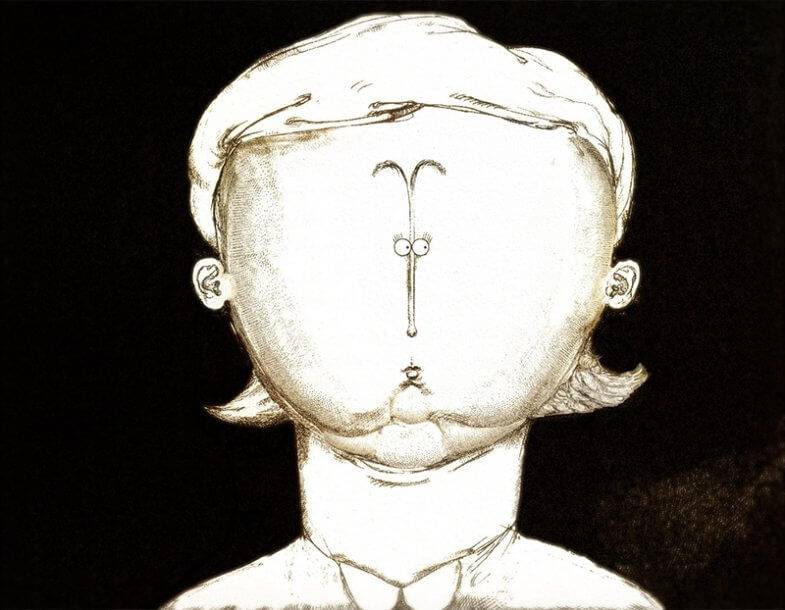

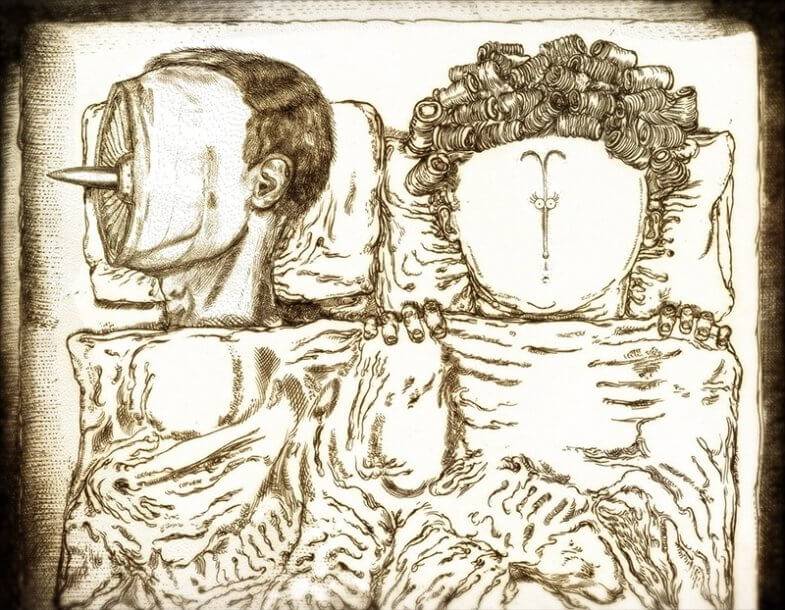

The film – a tragicomic tale in which a man has somehow fused with his crashed war plane and finds his romantic interests diverging from his wife and toward a ceiling fan – will see its world premiere this week at the Ottawa International Animation Festival (where his previous short Focus picked up an Honourable Mention for Best Canadian Animation in 2015) with October screenings at the Vancouver International Film Festival to follow.

Can you tell us a bit about your background and path to animation prior to your involvement with the NFB?

I grew up drawing all the time. Later, I specialized in medical illustration, but I had a need to funnel specific images in specific moments. Naturally, the animation career was the outcome.

When we first spoke you had recently concluded your involvement with the NFB’s Hothouse scheme having produced the film Focus. How has this experience and the film’s subsequent performance contributed to your career direction so far?

The experience of making a one-minute film with the support of the NFB at all stages of the production allowed me to wrap my mind around what it takes. Once this is done, you can feed it some proteins and expand to more complex projects with more confidence over the direction the product is taking as a whole. I’ve said this before, but our Animation Studio here in Montreal represents an indispensable sensorial lab, an invaluable space for experimentation and risk. I think being exposed to this philosophy emboldened the creative side of me.

What were the production circumstances that allowed Turbine to get off the ground?

Turbine had fermented for countless years in strange forms. I had some dreams, and the seed grew into a web of parallel worlds that mesh, mixing epochs and characters. Sudden shocks in the fabric, like a war, would fracture these parallel ducts, and characters could travel between worlds, their inward bodies levelled with external places like apartments and factories.

So solidifying a proposal to realize Turbine felt like taking a snapshot or documenting a portion of this. Producer Jelena Popović, with the invaluable input of filmmaker Theodore Ushev, listened to my stories and helped me funnel things into a cohesive moment or a self-sufficient portion.

The main visual motif of the film is very striking. Can you elaborate on how this developed?

Thanks. The ‘aerodynamic man’ has feelings, but not in our paradigm. The best analogy is if you visualize having a dog for a pet, and then compare it with having an iguana or a praying mantis for a pet. While the dog clearly has affection and greets you at the door, the iguana or mantis is simply there, still aware of you, but in a completely different field of existence. In similar ways, the turbine is a mute retina, and you’re looking into the face of a cyclops with motivations that can only be guessed because there is no actual facial muscle to help you read his mind.

The end result in Turbine is a very appealing combination of full and asset-based animation. Can you talk us through how you went about the animation process for the film?

Thanks. It’s observable that there is an uncanny (and seemingly arbitrary) juggling between ‘collage’ and fluid organicity throughout the film. I was hoping to make a bleeding book, heavily inspired by some of these anatomy flipbooks in the children’s section of libraries. My mother, children’s book illustrator Daniela Zekina, assisted me in making these assets deriving from the tradition of eau-forte, copperplate etchings. Although you have rigid plates of information dragged around, erosions of full organic behavior would pour out, like the joints of these plates, moving the characters through the environments.

Did you develop this unique illustration style specifically for the film?

When I made it, I didn’t know the images had a style. It felt like creating sober instructional illustrations of real things, with an honest attempt to simply survey their opaqueness and shadows in a photorealistic world. Just like I focus on the water instead of on my body when I swim, it works not to think of style, but simply on the subject matter that is being drawn.

Although there is an understandable narrative, the surreal elements of the film suggest a slightly freer approach to story. Did the story evolve/develop at all as the film/storyboards came together or was it rigidly in place when production began?

It was rigidly in place when production began. Bridging different moments and being as clear as possible on what is actually going on were the two incentives for any alterations that followed the ‘urban plan.’ Since there is no narrator and the sound followed the image, we had to be extremely clear in the actual visuals, as if visualizing the necessary steps for assembling a chair in the Ikea manual.

What were some of the main differences between the experience of creating Turbine and your previous film?

In Focus, you place a webcam and turn it on, and then this moulting body moves in front of the camera. The subject in focus, practically an invertebrate in ecdysis, is shedding, routinely casting off parts of its body at specific points in its life cycle. This chaotic anti-identity is ‘allowed’ because there is narration. For Turbine, we need to narrate by showing what is going on. This changes everything, and the moulting becomes the camera’s responsibility. So the subject is static (the opposite of Focus) and the camera is moving around.

Turbine, as opposed to Focus, also looks deeper into my Eastern European roots in Canada.

Recently you participating in our readers’ Q&A with legendary director Jan Švankmajer – has he been a major influence on your own work?

Yes, in many ways. While his films abound with science, his unusual imagery possesses an accessibility anchored in our shared subconscious language, making his films equally rewarding to the culturally informed and to young kids who simply enjoy visual stimulation. I am particularly attracted to the idea of seeing people as food.

Are there any other animators/illustrators/artists that have been crucial to your own artistic development?

I grew up with the Disney films, and love the classics.

You previously mentioned another project you had on the boil called The Mill – are there any updates as to how this is coming along?

I have been exploring ways of creating this next film, and I’m considering some stop-motion along with drawings. The Mill will be another surrealist comedy (fake “TV news” documentary) depicting a mosaic of situations in a seemingly detached arbitrary sequence. It’s really about how situations make good people do questionable things. I’d like all of it to maybe bathe in Edvard Grieg music.

Do you have any other in-progress/upcoming projects you are able to talk about?

I am working on a collection of animations, all indiscriminately named U+2672 ♲. I scatter them across the depths of the web, most often in GIF format.

Turbine will premiere at OIAF on September 27, 3pm, repeated September 30, 1pm.

For more on the work of Alex Boya visit alexboya.com