A Conversation With Adam Elliot

Adam Elliot

Adam Elliot is an important animator – a descriptive term rarely attributed honestly to practitioners of a medium whose primary function is, more often than not, frivolous entertainment. We can certainly be amused, moved, even angered by animation; we can be awed by its spectacle and its ability to communicate concepts which live action and other means of storytelling simply cannot. Ultimately though, like any form of artistic expression, it is ephemeral, its appeal just as bound by shifting cultural attitudes and political climates. As such, there is an inevitably smaller percentage of animators whose work has a lasting value, either through technical advancement or social messages. While Adam Elliot’s work, on an aesthetic level, is purposefully entrenched in a traditional and pleasingly nostalgic era of claymation, as a storyteller he undoubtedly falls into the latter category.

The director of four independent shorts – including the 2003 Academy Award winning ‘Harvie Krumpet’ – and his first full-length feature ‘Mary & Max’ in 2009, what has so far tied all his work together is an underlying theme of living with affliction. As put forth by his creative partner and former producer, Melanie Coombs, in the latter film’s EPK “I see the pattern in all of Adam’s work is about accepting difference. That we all look for acceptance and love is probably a universal truth; that we are all different, is another.”

Image courtesy of Adam Elliot Pictures

Born in Australia and a long-time resident of Melbourne, his films also have a shared sense of national identity, in a manner similar to the distinctly British politeness of ‘Wallace & Gromit’ and the celebration of American culture and family values that was ‘The Simpsons’ in its heyday. It’s a quality that, alongside the bold choices of topics covered in his work, has made Adam such an important figure in contemporary Australian film and culture.

While the world of mainstream, Hollywood animation is awash with lavishly produced, high-end CGI and visual effects, the world of stop-motion has become a strangely niche one. Though still a long way from being considered antiquated, the use of hand-sculpted/crafted puppets is considered a rarity within contemporary cinema. Its mainstream outings such as Henry Selick’s recent ‘Coraline’ (2009) and Peter Lord’s upcoming ‘Pirates! Band of Misfits’ (2012) are notable for being in scant company. In some respects it is a contributor to preserving the charm and uniqueness of the medium, and a testament to directors such as Nick Park, the aforementioned Selick and Lord – and, on the independent end of the spectrum, Adam Elliot himself – that it has been kept alive. What sets Adam’s work apart though is the juxtaposition of a look associated mainly with children’s animation against storylines and dialogue that are for a distinctly adult audience.

“I’ve just tried to tell stories that I’d want to hear, that are a little bit more edgy, the stories that push boundaries. You can do that with kids’ animation, for sure, but I don’t ever think about the audience too much. I just sit down and write stories that would appeal to me and then worry about who my demographic is. I’m not just the only person out there, which is great – films that have come out recently like ‘Waltz With Bashir’ and ‘Persepolis’, that type of animation is definitely evolving and shifting gear and there is more and more ‘adult’ animation. Although I didn’t use that term until recently, because if I did then most people would think I was doing films like ‘Fritz The Cat’, or some sort of clay pornography! Whereas now people are understanding that animation is a preference, it’s like a pencil or a paintbrush, it’s just a vehicle for telling a story, so why has it traditionally been geared towards children? I blame Disney for that! We’ve definitely progressed since the days of ‘The Lion King’ and ‘Aladdin’, but when your budget is a hundred and seventy million dollars or somewhere around there, you can push the boundaries a little bit but you have to be pretty safe. That’s a lot of money.

“I’m very thankful and grateful to companies like Aardman who’ve brought claymation to the masses, but I think I’d still be a stop-motion animator regardless of whether ‘Wallace & Gromit’ were invented. I can only talk from my personal experience, I suppose, but I do stop-motion animation for purely selfish reasons. I’m friends with Nick Park and Peter Lord and it’s good to catch up with them, but really the only thing we have in common is plasticine. I get very frustrated sitting in front of a computer screen, I’d much rather be chopping up wood or painting and getting my hands dirty, making all these bits and pieces for the films. I love the tactile nature of stop-motion, it’s just a personal choice.”

Alongside his affinity for plasticine animation, a consistency in Adam’s work since his beginnings as a student animator has been the casual incorporation of subject matter that mainstream television and cinema (even, to a large extent, the world of independent film) feels compelled to handle with kid gloves. Though no doubt well intentioned, this hypersensitivity toward the depiction of important social impairments, physical disabilities and mental illnesses has in many respects only served to fuel the sense of alienation that accompanies them. Adam Elliot’s storytelling, by contrast, indulges a far healthier and more socially aware impulse to bring these issues out into the open. Said issues span birth defects, Tourette’s syndrome, Asperger’s syndrome, cerebral palsy, alcoholism, depression and all manner of limitations of social and cognitive development. The undeniably tragic inherences of these afflictions are married with the far more taboo notion of their comedic mileage. Rather than cheapening or trivialising the plight of each character, this gallows humour instead rounds out and humanises all of them, making their stories all the more poignant.

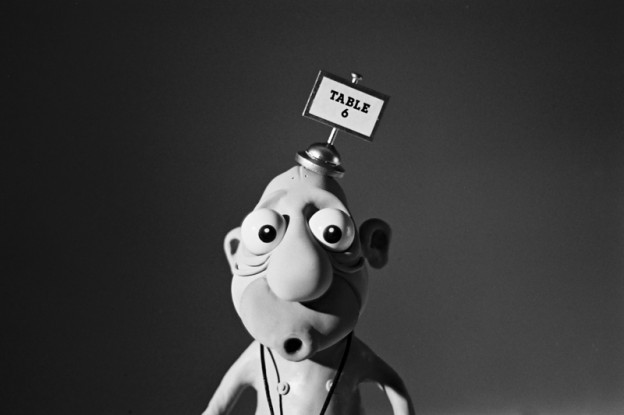

“I always try to write funny films, unfortunately I can’t help myself – they end up being quite tragic! No one has a perfectly happy life or a completely miserable one, I think it’s all shades of light and dark. Comedy-tragedies have been around for centuries, and to tell stories which are authentic, empathetic and relatable to an audience you can’t just do gags, you have to dig deeper. I try to create very authentic characters – which is ironic, ‘cause they’re plasticine – and while my aim is, of course, to make the audience laugh, I really feel like I’ve achieved something if I’ve caused them to cry. I know that’s a strange ambition, to upset your audience, but I don’t like them leaving the cinema indifferent or apathetic. I really want them to have experienced something – even if they’ve just laughed, at least I’ve pushed some buttons. I think ‘Harvie Krumpet’ opened the doors and really enlightened a lot of people, especially in my own country, as to what animation can be.”

The film, narrated by Geoffrey Rush, is centred on the life of Harvek Milos Krumpetzki, a Polish WW2 refugee who flees to Australia following the death of his parents. His existence is frequently blighted by misfortune, beginning with a diagnosis of Tourette’s syndrome at a young age, yet he remains throughout his life inquisitive and optimistic, albeit lonely. Inspired by the well-known aphorism ‘Carpe Diem’, he embraces life in as full a way as possible, sidestepping social propriety in favour of contentment and personal accomplishment. Against the odds he marries and begins a family, raising his adoptive daughter Ruby – “A little Thalidomide girl” – to similarly pursue her own ambitions. The final act of the film, dealing with his return to solitude in his autumn years, carries with it the most resonance. The nature of loneliness being both solemn and terrifying, one of the film’s overall messages is that it can only consume us if we allow it to.

“I am driven a lot by my gut instincts and intuition. I don’t read a lot of books on scriptwriting, I don’t obsess about three-act structures and I don’t go to seminars. I do watch a lot of films – too many films I think – I read a lot of biographies, I try not to hang around with too many other filmmakers, they depress me!

“I’m just fascinated by the human psyche, I love telling stories and biographies about my family and friends, which is why I came up with the word ‘clayography’; I never felt comfortable calling myself an ‘animator’ or ‘claymator’, so I thought “What do I do? I make clay biographies”. That’s what I wanna keep doing.”

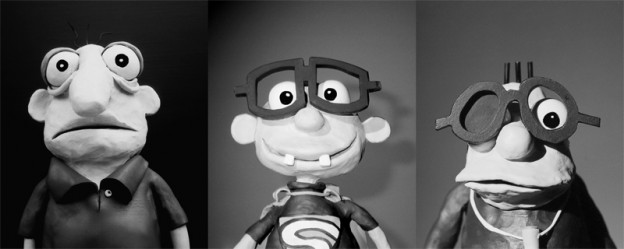

The title characters of Adam Elliot’s first trilogy of short films, ‘Uncle’, ‘Cousin’ and ‘Brother’ (Images courtesy of Adam Elliot Pictures)

The connections to family are especially strong with Adam’s original trilogy films, beginning with his 1996 VCA student short ‘Uncle’ and the AFC-funded follow-ups ‘Cousin’ (1998) and ‘Brother’ (1999). Firmly establishing his visual style and setting the tone for ‘Harvie Krumpet’ and beyond, the highly-accoladed shorts are similarly-themed, anecdotal recollections of each titular family member, narrated by Australian performer William McInnes. “I love films that are narrated, I just find there’s something really intimate and authentic and personal and real about them. I mean, there’s bad narration of course, but I really love that sensation of somebody guiding you through the film.”

In these shorts, the stories as told have an honesty and emotional weight to them that is rarely evidenced in plasticine animation, while the lines between fiction and non-fiction are purposefully blurred. Similar ambiguity is sensed in his eventual 2009 feature ‘Mary & Max’, which begins with the oft-debated, long-standing cinematic claim “based on a true story”.

“I never let the truth get in the way of a good story, there are plenty of embellishments, exaggerations and scenes that are completely fictitious. In a way, my earlier films were like flicking through a photo album; you just see little vignettes and photographs that happen to move and blink at you. Of course, with a feature you have to have some sort of storyline there. I’d had a desire to tell a story about my pen friend for a long time, I’ve got a big box of all his letters from the last twenty-two years and started to re-read them and realise what a fascinating person he was, and still is. I thought “Well, there’s so much here, this is easily a feature”. But then I didn’t want to put myself in the film, so I became an eight year old girl, just to make it a bit more extreme and, again, push the boundaries and make it a little bit more interesting.”

Still from ‘Mary & Max’ (Image courtesy of Adam Elliot Pictures)

The story of ‘Mary & Max’ begins in the seventies with Mary Dinkle, a bullied and outcast Australian girl with a distant father, alcoholic mother and an inability to make friends her own age. On a whim she begins corresponding with Max – a Jewish, middle-aged Manhattan resident with Asperger syndrome – after picking his address at random. Despite battling against health and anxiety issues, Max’s life boils down to the most rudimentary type of existence. After acclimating himself to the disruption in his routine that receiving the letter brings, he cautiously reciprocates, beginning a friendship that appeals by virtue of distance. Over time, Max and Mary become one another’s confidante, and their correspondence serves as an anchor for all the major events of their lives. As a feature-length film, the grander scale of the story lends itself to a greater degree of emotional investment in the characters as we see their lives grow warmer and more fulfilled.

Images courtesy of Adam Elliot Pictures

“I’ve never obsessed about length – like my Mum always said it’s quality, not quantity – I only let my characters tell me how long their stories are going to be. I started off thinking ‘Harvie Krumpet’ was gonna be a five-to-ten minute film – by the time I’d finished writing it was more like a half-hour. That’s why we made it that way, we didn’t worry that it was long for a short and could be very difficult to get into festivals, we just focused on telling the best story we could. Of course, when it won the Oscar that opened a lot of doors and made it more viable for me to attempt a feature. I never thought I could make one but now that I have I think “Oh, actually it’s not that hard” – I mean it is, of course, incredibly hard (laughs) and hideously expensive, but now I’m sort of getting familiar with the structure of a feature film. I feel more it’s that sort of length I want to keep pursuing.”

Lending the film even greater credibility is its staggeringly high-end voice cast, led by Academy Award winner Philip Seymour Hoffman as Max. As an actor who has so effortlessly and frequently taken on the role of beleaguered, social misfit, it is largely thanks to the more recent turns in his career that have steered him away from the precipice of being typecast. In Max, though, this return to the well is a perfect choice, drawing upon his known abilities as a live-action performer and extending them into the world of voice-over acting. The film’s supporting Australian cast features Oscar-nominee Toni Collette as the adult, world-beaten Mary and Eric Bana as Damien, her stammering and internally conflicted love interest, while narrated affectionately throughout by the legendary Barry Humphries.

“With each film I’ve had actors in mind even as I’m writing. I didn’t necessarily want them to be big names, just voices that I thought would suit, thinking there was no way I’d get them. We never thought we’d get Philip Seymour Hoffman, that was almost a joke! We kept forgetting that, because of the strength of the script and the leverage of ‘Harvie Krumpet’, we did have access to these people and that they would at least contemplate reading it. Casting is important but I don’t think of actors just so we can help sell the film, of course a name like Philip Seymour Hoffman does help, but it’s not the reason I wanted him for the voice. I just like an actor whose star isn’t brighter than them, who have a sort of credibility, an actor’s actor. So yeah, he was always the first person in my mind, he’s a chameleon and he just seemed like a perfect match. Toni Colette, she’s got a melancholy and vulnerability to her voice, she seemed a right match there, Barry Humphries, too, he has this certain warmth as a narrator that I felt was appropriate. So yeah, all the actors we wanted, including Geoffrey Rush for ‘Harvie Krumpet’, we ended up getting. Certain actors, you could listen to them read the phone book, y’know?”

Harvie Krumpet (Images courtesy of Adam Elliot Pictures)

The bulk of the cast recordings were done in Melbourne, with Seymour Hoffman contributing from the UK via an internet feed, “Just because the cost of flying him here first class and putting him up in hotels and limousines – all those things that agents demand, not so much the actors – would have blown our budget completely. So we recorded him remotely, it was a very expensive hook-up with no delay that we had between the two proper sound recording studios. I was very sceptical at first. I thought “Oh no, look, as a director I really need to be there with him”, but after recording it he enjoyed the process, I enjoyed the process, I could focus more on his voice and not have to worry about if he was being fed or getting cups of tea, that sort of stuff. So I highly recommend all directors direct their actors from the other side of the planet!”

Another crucial and sometimes overlooked cast member was Bethany Whitmore, whose solemn and endearingly naïve performance as the young Mary in the earlier parts of the film cemented the character’s sense of loneliness. “With all these rules and regulations about working with kids, I think we ended up having at least six or so recording sessions with her – I think the end result was worth it. We’d auditioned forty or so little girls for the part by the time she came along. She just had this melancholy to her voice, this honesty, it was a very authentic sound.”

The film’s soundtrack is an expertly interwoven selection of songs by a range of artists including Pink Martini and Penguin Café Orchestra, alongside classical music and original cues by composer Dale Cornelius. Alternating between jaunty folk-jazz, brooding orchestral dirges and uplifting fanfares, the somewhat bipolar end result complements the tone of the film – and in many respects, that of his previous shorts – perfectly.

“My first three films had no music at all, so in a way music is something I’ve only just sort of discovered. Sometimes it’s just serendipitous that you’ll be writing and there’ll be something on the radio that just seems to match up with it. There are a few scenes in ‘Mary & Max’ where the music was chosen purely for that reason. It’s hard to even articulate why certain pieces of music work for certain scenes or montages. I’m not a big fan of getting composers, the majority of the music I’ve had in all my films has been from CDs. Then it’s just paying the licensing and getting it mixed right and synced up. I do love classical music – which is pretty obvious from the films – but I really seek out music that is nourishing, that just on its own seems to have a potency about it, that can be either very melancholic or very uplifting, push your buttons and stir something inside you. If you’ve got a vision and some good animation, you just cross your fingers and hope that they work together.”

With ‘Mary & Max’ having far less shrouded real-life derivations in comparison to Adam’s earlier films, an obvious point of curiosity is in regard to one particular member of his audience; The long-standing pen-friend on whom Max was largely based.

“We were very transparent with the film when we were making it, so he knew all about it. He couldn’t see what the fuss was about, and when he finally did see the film he sent me a list of things he thought could be better, in true Asperger’s fashion (laughs). He’s still confounded as to why anyone would want to make a film about him – he’s much more into mainstream films. I’m looking forward to meeting him for the first time this Christmas, neither of us thought when we started writing letters to each other that I’d end up making an eight million dollar film about our letters! It’s amazing how art can imitate life and vice versa.”

The bleaker and decidedly less comedic parts of the story also carried with them a less appealing, life-imitating-art potential. One of the film’s crucial story points, where Mary’s own endeavour to bring their relationship to the public, is met with hostility and feelings of betrayal from Max.

Adam Elliot on set of the massive replica New York built for ‘Mary & Max’ (Image courtesy of Adam Elliot Pictures)

“I deliberately wrote that scene because I felt that it would be funny…well, not funny, devastating (laughs) if I made this film that he disapproved of! It was quite a bit of a mindf**k to write something in that way, quite risky and quite dangerous, but I like to sort of play around with concepts and ideas, things Disney and Pixar would never do.”

In the wake of his recent successes, the name Adam Elliot has developed a new weight on an international level. Deluged by unsolicited scripts, directorial offers and collaborative opportunities within Hollywood, Adam has remained faithful to his roots as an independent Australian director, though out of necessity in some respects. After shopping ‘Mary & Max’ to major US studios and being met with consistent disinterest or overcautiousness – “We tried to pitch ‘Mary & Max’ to Disney, it was like we were pitching a snuff film!” – the movie wound up being produced, fittingly, on his home soil.

“We’re very lucky that we have government investment here in Australia, we have fantastic tax rebates for filmmakers. Nevertheless, it’s very slow and complex to raise the money; Australia’s a small country, we only have twenty million people and philanthropy is not one of our strong points.

“We always see ourselves as somewhere between Europe and America; we have an English sensibility but we tend to try and sell ourselves to the Americans. We complain, but compared to other countries in many ways we’re doing okay. In terms of the industry we tend to punch above our weight. Melbourne seems to be very conducive to creativity, we have a lot of independent animation and Shaun Tan won the Oscar this year for ‘The Lost Thing’. Maybe it’s to do with the weather here being so lousy that we spend a lot of time indoors, there’s not much else to do!

“With my budgets getting higher and higher, the sad reality is that I do have to leave our shores to seek other investment. The thing that gets me to where I wanna go is credibility; no-one ever invests in my films because of the previous box office success. The Oscar we often call the ‘Golden Crowbar’, because doors do open and it makes it easy to get scripts read by people. I’m always reminding myself of how lucky I am, in that I have access to investors, I’m very privileged in that way. But it all comes down to a good script, I obsess about them, I write multiple, multiple drafts, I get the thesaurus out for every single word (laughs) I probably polish a little bit too much, but that’s where it all begins. If you don’t lock off a good script before you start, especially in animation, then it’s really hard to end up with a good film.”

Mary’s alcoholic mother, Vera. (Image courtesy of Adam Elliot Pictures)

“I think I’d upset people who’ve liked my films if I suddenly jumped ship and went and worked for a big studio. I’m pretty sure I’d never come back, I’d get attached to the money. I do go to Hollywood every now and then to meet with potential investors and studios, but they all say the same thing to me, “Oh, we really love ‘Harvie Krumpet’, we really like ‘Mary & Max’ – do you wanna do this film about flying dragons?” (Laughs) I mean, my aim in life is to never have any of my animals talk, I just refuse to, and unfortunately most high-end animation does have talking animals, so I’ll probably get to the age of sixty and look back and think “You idiot, you should’ve done at least one of those big CGI films, got yourself some superannuation, something to retire with!” I’m not anti-Hollywood, I go and see ‘Toy Story’ and all those sorts of films like everyone else, but I’m almost forty this year and I think I’m becoming more of a stick in the mud, more of a purist.”

Despite keeping ‘Mary & Max’ as an independent Australian feature, the move served to keep the story intact and unfiltered, with the film being tremendously well received on its release. After being picked as the opening film for the 2009 Sundance Film Festival (a first for both animated and Australian cinema), its ensuing festival tour and worldwide release garnered overwhelmingly positive reviews from critics and audiences. Yet despite the success and respect within the animation and filmmaking industry, it sadly didn’t follow in its predecessor’s footsteps and was passed on by the Academy Awards. More bizarre still, it was unable to pick up a significant theatrical run in the States.

“I learnt a lesson, which was that America’s still quite conservative in many ways. I see it as a very uplifting film, Europe sees it similarly, but in America they see it as very dark and are obsessed by saying “Not for children!” Now that I’ve had some hindsight and can be objective I know why we didn’t get a bigger release, I don’t blame America at all for not putting us out at all the multiplexes.

“The irony is that we know ‘Mary & Max’ is thriving out there – on DVD, on airlines, as a pirated film – it’s alive and kicking and seems to be growing more and more. Critically we’ve done really well, it has a very high average rating on sites like Rotten Tomatoes and IMDB, which is gonna help get the next film financed. We’re getting more emails now than when the film was released two years ago, especially on Facebook. The comment we get the most is “This is not what I expected” and I think, “Well, what were you expecting, ‘Finding Nemo’?” (laughs). We also get some very sad emails from people, especially parents of kids with Asperger’s syndrome and people that are terribly alone, who relate to Max and to Mary, some of them are very hard to read. So we know that we’ve made a film that affects people quite deeply, yet why couldn’t we convince distributors to get it into cinemas? At the time I didn’t think we were creating another ‘arthouse’ film, but in the end we sort of did.”

Max types while wearing a gift from Mary, an example of Elliot’s frequent use of spot-colouring (Image courtesy of Adam Elliot Pictures)

A further testament to the film’s resonance among the public are two proposed stage adaptations currently in the works, one in Brazil, the other in Germany.

“At first I was a bit apprehensive, but then it was like “Ah, look, why not?” It will be interesting to see how they go about it, I don’t know much about where either of them are, what stage they’re at or what sort of budgets they have, but I think it’d be interesting to see them interpret it. I much prefer the film be turned into a play than a TV series, I think there’s a little bit more credibility about a stage play, regardless of how bad or good it might be. I love the theatre, I think because it’s so immediate and spontaneous, whereas making a stop-motion film is like watching grass grow at times. It’s insane when you really think about it, it’s just…who would do what we do? It should be banned! I always sort of compare it to one of those signs that says ‘Wet Paint’, you can’t help yourself but touch it, you know it’s wet, yet you’re drawn to it. It’s such an indulgent, slow, expensive pursuit, just for an hour and a half of celluloid that will be projected, to make people laugh? I mean, you’d go mad if you obsess about it like that.

“For me, the way I see this is that I’ve made five films, they’re still alive, they’ll forever be on the internet after I’m dead, I presume. ‘Harvie Krumpet’ still just seems to keep going, he never seems to die! They’re like children you’ve given birth to, who leave home and every now and then come back asking for money, but they’re off having wonderful lives and you’re just the parent back at home, trying to survive and get pregnant with another child.”

The success of these ‘children’ speaks for itself. On top of the Academy Award, Adam’s five films to date have accrued a staggering number of prizes (well over a hundred, including five AFI awards and the Annecy Cristal in 2009) and screenings, making his work coveted as a staple of the industry and festival circuit.

“Festivals are wonderful, hedonistic ways to meet with other likeminded people, and you always get a buzz out of seeing how they react in different countries to your films, you learn a lot about what is universal and what is idiosyncratic to each country. When I was younger I did like going to Annecy and any festival who invited me as much as possible, but I think now that I’m getting older I find myself turning down some wonderful invitations. They especially want me to be a juryman now, they think that once you’ve won an Oscar you’re an expert and that you can tell a good film from a bad one. I really am reluctant to do any of that – who am I to judge other animators’ work?”

Image courtesy of Adam Elliot Pictures

Adam’s most recent project is conceivably closer to the ‘Disney’ wheelhouse his films have yet to occupy: a family friendly – though stamped with his trademark penchant for misfortune – book of short illustrated poems. Bearing the self-explanatory title ‘The A-Z of Unfortunate Dogs’, it became an instant bestseller over the 2010 holiday period.

“That was something I did after ‘Mary & Max’ where I felt like I wasn’t ready to start writing again. I love to draw, I’ve got dogs and people have always asked me “Why don’t you do a book?” So I thought, “Oh, well, I’ve got a whole collection of dog drawings, I’ll see if I can put something together”. I didn’t have a publisher, but once it was finished I thought I might as well start at the top and see if Penguin books liked it. Luckily they did! It’s done pretty well in Australia and they want me to do another one, I don’t want to switch careers but it was quick and cheap which was very satisfying! One day down the track I’d like to put together a compilation of all my drawings, no story, like a coffee table book or something, but I’ll probably wait another five or ten years before I do that.

“Tim Burton had an exhibition here in Melbourne last year, which was previously at MoMA. It was amazing to see all of his original sketches, to have an insight into where all of the ideas came from, especially his earlier films, all the puppets from ‘Nightmare Before Christmas’ and ‘The Corpse Bride’. I think I’m too young to have a retrospective yet, although I’ve had a few for my films, which I find bizarre (laughs). I didn’t think I’d be having retrospectives until I was in my seventies, so it’s quite flattering.”

Looking forward, Adam’s forthcoming film – another feature – will mark his return to self-producing, following a successful partnership with Melanie Coombs of Melodrama Pictures, who produced ‘Harvie Krumpet’ and ‘Mary & Max’. Presently titled ‘Ernee’, the film recently earned investment from Screen Australia and will be a first for Adam in one vital aspect: “It could be the worst decision I’ve ever made, but I feel as though I might be getting a bit formulaic by using narration, so the new film I’m writing at the moment I’ve decided won’t have any. It’s a bit of a deviation, though it’s definitely my style of aesthetic and subject matter. It’s my version of a romantic comedy – I don’t think it would be seen that way by many others, but it’s probably as close as I’m ever gonna get to that genre. There’s plenty of dark stuff but I think there’s more light when compared to ‘Mary & Max’. The budget we’re sort of aiming for is somewhere between fifteen and twenty million Australian dollars, which is still pretty cheap compared to Aardman or Pixar. It’s definitely not the level of ‘Pirates’, for example, but it is an advance from ‘Mary & Max’, a bit more dynamic. I think it’s going to take us at least another six-to-twelve months to finance, and then of course another two years to make. I’m sort of averaging about two films a decade at the moment so I’ve probably only got four left and I’ll be dead! I’m confident ‘Mary & Max’ won’t be my last film, but we’ll see.”

As enlightened as we assume ourselves to be, to this day a contingent of society remains cowed and even angered by what is considered abnormal or out of their immediate realm of understanding. These attitudes were evidenced in the UK as recently as February 2009, when the BBC received more than a handful of legitimate complaints (accompanied by a larger outcry on associated web forums) in regard to Cerrie Burnell, a children’s television presenter whose right arm is visibly less developed than her left. Prompted by their children’s inquiries, some parents cited their discomfort at having to explain the woman’s disability, accusing the BBC of being motivated by political correctness to fill minority quotas. Naturally these reactions and claims were dismissed for their ignorance and fatuousness, but even with the hope that they stemmed from a vocal minority, the concern remains. It is with this in mind that some of the most positive applications of Adam’s films has been their incorporation into the senior English curriculum of schools throughout Australia, as well as their use as educational aids the world over for their fundamental messages of positivity in the face of life’s hindrances, be they informed by physical disabilities, mental impairment or simply not fitting in. As Harvie Krumpet himself summarises to his daughter, “Some people have less bits, some have more bits; Everybody is unique”.

“A journalist asked me recently, “What sort of legacy would you like to leave behind?” and I thought “What a question!” Then I realised, well, I suppose a legacy is leaving behind films that have some value, that people get a positive reaction from. I don’t make schlock films, I don’t make films that have a negative impact, they might depress some people, but again I see them as uplifting and nourishing and universal and hopefully, to a degree, timeless. I just wanna make sure that when I’m dead and buried I haven’t just made a whole load of shit in my life, y’know? I do like to do things my way, but at the same time I don’t want to become stale and stagnant, I’d rather push myself and my own storytelling as much as I can, without compromise and without alienating my audience, which is a tough thing. I think a lot of filmmakers run out of steam and I’m always worried that each film I make could possibly be my last. I’m sure I’ll make a couple of films that are bombs, but hopefully the bulk of what I’ve done has some value to people.

“That’s if we’re around in a hundred years’ time. Who knows?”

‘The A-Z of Unfortunate Dogs’ is available from Penguin Books. Further info on the works of Adam Elliot can be found online:

- Adam Elliot Pictures http://www.adamelliot.com.au

- ‘Harvie Krumpet’ Official Site http://www.harviekrumpet.com

- ‘Mary & Max’ Official Site http://www.maryandmax.com

Items mentioned in this article:

![Harvie Krumpet [DVD]](https://www.skwigly.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Harvey-Crumpet-dvd-cover.jpg)

![Mary & Max [DVD]](https://www.skwigly.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Mary-and-Max-dvd-cover.jpg)