Acting For Animation: Character Development

How to get under that character’s skin

Last time we looked at observing, rehearsing and timing to help you to prepare your animation. As a result you should now be avid people watchers as well as being more observant of your own movements, more comfortable with rehearsing these moves in front of a mirror and better prepared when it comes to timing (and recording) your movements. But what about the characters themselves? Who are they? What do they do? And, where do they come from?

When you are working with a new character they will always be a little one-dimensional until you get them fully developed. Now this character might be one that you are given to work with in a series or a film, in which case the director will have helped to develop them to a degree. Or it might be one that you are coming up with from scratch in a storyline of your own. In both cases the process of evolution begins with character development, by interrogating them, not with bright lights and cattle prods, but by finding out a little more about their personality, temperament and hopes and fears. All of these will affect who they are, how they react and therefore, how they move. For you to get the best possible performance then you need to be able to act with conviction and to do this it helps if you understand the process of character development. It is vital that you know about the characters you’re working with, and an interrogation of them will enable you to develop a better understanding of what sort of reactions, feelings, and physical, emotional, and psychological responses to the other characters, and situations in the film they will have. If you as an animator have a good grasp of different personalities then this will assist you in the process of the interrogation. If you are working with a director then they should be able to give you some of the characters background, but you should also study the script and the vocal performance. If you are working on your own though then it’s down to you to create this background, and to get to know the characters as well as you would a friend. In both instances it’s about figuring out the nature of characters, having empathy, being observant and imaginative.

Having interrogated your character I would then suggest that you try to deconstruct your characters, relating them to your own experiences and your empathetic understanding.

Still from ‘Frankenweenie’ (Warner Brothers/Tim Burton Animation Co.) Understanding your character is critical when you get to animate someone like Victor as the performance has to be spot on – as good as any other actor in a Hollywood feature.

A character can be deconstructed in four main ways – the way that they act/react (mannerisms, idiosyncrasies etc), the way that they speak (idioms, accents, volume etc), the way that they look (physical appearance, clothing etc) and the way that they think (beliefs, passions, opinions etc). I think that you can separate out a characters actions and reactions from the way that they think when as an animator you try to figure out just what your character is all about. For you to get going with figuring out your character it helps if your main focus is upon the visual and aural elements, as these are the foremost clues to identity that you have to work with. The vocal performance not only dictates the rhythm and pace of a characters movements as the intonation changes, but the timbre of the voice will help shape the way in which the character holds themselves. A slow, gruff and mumbled delivery may well suggest a sluggish and hunched person for example, whereas a bright, sharp and well paced delivery may suggest the opposite, someone who is young, keen and energetic. Visually you will be guided by the design of the character, and unless specifically directed otherwise your performance would be expected to conform to type. This means that if an animator is given a frail old woman to animate then the actions, movements and gestures should reasonably fit within the stereotype that we have for them. The vocal performance (if applicable) will only help to reinforce this.

I always found it helpful as an animator to be given a ‘bible’. This is something that the director or producer creates to give each animator a clear idea of what each individual character is about. The ‘bible’ should give a bit of the back story, and tell you how each character behaves, what their nature is like, what they love or loathe and whether they have any little idiosyncrasies that you need to be aware of. What a ‘bible’ helps to do is bring continuity of movement, each individual character moves in its unique way no matter who animates them.

Have a clear understanding of where the character comes from

Just as a script writer or director will have created something of a back story for each character then you as an animator need to take this back story and weave it into the personality of the character. A writer may imbue their character with certain traits but it’s your job to realise these subtleties. Most working animators will find that they are given a character sheet, or a ‘bible’, a reference framework that outlines the broader aspects of a characters personality. This should include a list of idiosyncrasies that the character possesses. The idiosyncrasies the characters have help define their individuality. Look at the performances in any of the silent comedies from the 1920s & 30s, and Laurel & Hardy. They used idiosyncrasies as a kind of shorthand so that we know that when we see Oliver Hardy ruffle his tie we know he is slightly flustered, and in the same way Stan Laurel scratches the top of his head in an overly exaggerated way we get that he is confused. These actions were peculiar to those individuals alone, and with them they carried their own meaning which was understood by the audience. This is an important notion for you as a character animator to grasp when performing. You will need to develop a set of idiosyncrasies actions, and for these to be successful these should be weaved around the dialogue if it exists and where it is applicable (remember that you need to keep an authenticity to your movements and gestures). Idiosyncratic actions should mirror the way dialogue is delivered and should serve to reinforce the audiences understanding of the character. Such idiosyncratic actions could include a nervous twitch when anxious, hitching up their trousers when determined or a tendency to nod, eyes closed, when listening to others.

Still from ‘The League of Gentlemen’s Apocalypse’ (Universal/Tiger Aspect/Film Four). Understanding this character was complicated as it had three heads – those of Mark Gatiss, Reece Shearsmith & Steve Pemberton but also had to move like a Ray Harryhausen beast!

Your challenge is to interpret the dialogue and to work from the back story and ‘bible’ combining it all into a set of readily identifiable gestures. The back story will be outlined to you by the director and a close eye is kept on ensuring that there is continuity, especially amongst a team of animators, to each characters gestures. To a degree there then becomes a bank of gestures associated with each character that you can draw upon. Every animator, even with the best will in the world, will bring small elements of their own personality into the character that they are animating. It is this that makes each performance unique. The skill of the director is to ensure that this is kept within reasonable bounds, within character. If you are a single animator working in isolation then you will not experience this variance in performance. But you still need to be aware of the impact of your own personality on the performance. In short, it is vital whether working as a team or alone that the back story is constantly borne in mind as this is what should drive the way that your characters act and react, the way that they speak, the way that they look and the way that they think all of which will influence the actual of performance.

Who does what and how?

Now whether you study the theories of Aristotle or Vladimir Propp1 you can reckon on there broadly being about 10 main character types (although Theophrastus2, a student of Aristotle identified up to 30). With a bit of research you can use these as a way of deconstructing a character in order to understand what motivates them, which in turn lends to a greater understanding of the personality. With more knowledge of just who a character ‘is’ then you should be able to create a better performance. It might help you to get to know your character a little better if you can pigeon-hole them early on, defining them by their type and so figuring out how they are more or less likely to behave/react/interact. Here is a quick summary of the main ones to look out for:

Protagonist – this is the lead character, a hero or heroine, in any film or story. Usually the protagonist is the champion of an idea or cause, whether wittingly or not. In most cases the film will centre around them and their struggles.

Antagonist – this character is kind of the polar opposite of the protagonist and someone who tries to thwart their ambition. Sometimes the antagonist doesn’t even have to be a character, it can be an event or organisation pitted against the protagonist, and their purpose is to show up as an opposite of the protagonist, what they stand for or want to achieve.

Symbolic Character – as the name suggests a symbolic character is there to represent something, a set of beliefs or ideals, a moral, ethical or religious code.

Confidante – the confidante is a tool to help explain to an audience what the main character’s personality, thoughts, and intentions are as they confide their hopes and fears to them.

Dynamic Character – these characters start off as one type of person, and end up as someone different at the end of the film. The events in the film affect this change, which is usually permanent. These characters can be a useful foil to the protagonist at the start where a sense of tension and conflict can be suggested.

Flat Character – not a lot goes on for the flat character as we don’t get to know much about them, maybe one or two traits and that’s it, and that’s why they’re pretty flat! But they still serve a purpose, mainly in supporting roles.

Round Character – these are usually the opposite of the flat character and are a pretty well developed character, and they are likely to change in some way during the story. You might also find that the round character shows a number of, and sometimes, contradictory traits. They are often dynamic in nature too.

Foil – the foil character is used as a contrast to another characters personality, their personality being at odds and in opposition to that of (more often than not) the main character. Sometimes a foil can also be the antagonist as this fits in nicely with their function in a story.

Static Character – even more flat than the flat character! This is a character that stays pretty much the same throughout the story. Nothing really ever changes who they are.

Stock Character – this is always a fun character to work with as this is where you get to play as a bit of a stereotype, as it’s that stereotype that makes them easy to identify. In animation there’s the chance here to push this a little further than normal too, to exaggerate the performance.

Now of course these are general types, and as you look at different film genres in more depth then you will discover that each genre has its own specific character types – film noir famously has its femme fatale and every musical it’s leading lady. It’s for you to decide (if it’s your own project) which genre you work fits into, and from there to establish which of your characters fits which character type.

Still from ‘The Koala Brothers’ (Spellbound Entertainment/Famous Flying Films). Understanding the different personalities is key to getting each character to move in their own unique way.

However, the behaviour of your characters needs to be based on your knowledge of human psychology (no matter how basic this is) as well as your own experiences. Every character animated will be a reflection of some aspect of you whether you realise it or not! Avoid copying a performance that you have seen, appropriating gestures yes, wholesale reproducing Olivier’s ‘Hamlet’, no! You need to be able to draw upon your own experiences in the same way that you understand movement through observation rather than by rotoscope. If you want to develop as a character animator you will need to get into the mind set of the character that you are to animate and picture the scene unfolding as if from a film. Listen to the dialogue while you’re doing this and remember every facial nuance, flick of the hand or shrug you act out or imagine. Most importantly you must do this as the character you have interrogated rather than doing it as you. Get inside your character.

When it comes to preparing the movements of your character, specifically in relation to using dialogue then you need to have a clear understanding of the intentions of the text. You’ll find that this is partly the responsibility of the director to explain this, for sometimes what is left unsaid in a conversation can be the most crucial. Subtext can often be used by a scriptwriter to suggest deeper issues between a set of characters without having to actually reveal it. It is vital therefore for you to have grasped the subtleties of the script before committing it to film. Make sure you discuss this with the director so you are clear on how the character should move, adding authenticity to the script, and directors make sure you brief your animators thoroughly! All subtext needs to remain as just that, but with a clear understanding of personalities and type you should be able to convey the realities of the text whilst restraining any inclination towards betraying the subtext. That said, there may be occasions where a director wants a little information from the subtext to be drip fed to an audience.

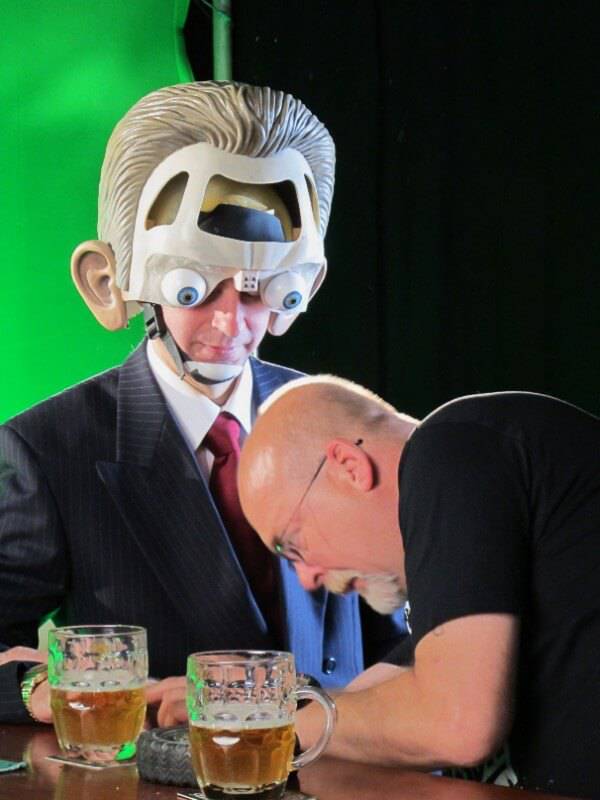

Still from ‘Bob’ (Passion Pictures/Darren Walsh). Animators will sometimes have to work with life size characters, or sometimes people. As an animator you need to keep control of the performance, and understanding who your character is will be a key part of making that performance work well.

Clear direction is paramount then. As is good listening, interpretation, imagination and realisation on the part of you as an animator.

In my next tutorial I will be looking at how you work with dialogue, both as an animator and as a director, how to get the most from the performance and getting the performance to match up.

1 Propp, V.I.A. (1969). Morphology of the Folk Tale. Texas: University of Texas Press

2. Theophrastus (2003), Characters. Translated by J. Rusten. Loeb Classical Library