Aardman’s “Lip Synch” 30th Anniversary Interview (Part 2)

This week on Skwigly we continue our look back at Aardman’s game-changing Lip Synch series with part two (catch up on part one here) of our interview with Aardman talents Peter Lord (War Story, Going Equipped), Barry Purves (Next), Richard ‘Golly’ Starzak (Ident) and Aardman co-founder David Sproxton. The transcript that follows has been edited for length and clarity ahead of the full interview’s inclusion in an upcoming Skwigly Animation Podcast.

Aardman staff in Wetherell Place (image courtesy of Aardman) –

Front row L-R: Peter Lord,(Director/Animator), David Sproxton (Director/DOP)

Middle row L-R: Melanie Cole, (Admin/Assistant Producer), Sara Mullock (Producer)

Third row L-R: Andy MacCormick (Cameraman), Jeff Newitt (Director/Animator), Rich ‘Golly’ Starzak (Animator/Director), Glenn Hall (Technical Wizard)

Back: Alan Gardner (Production Assistant)

David Sproxton: The commission [for Lip Synch] actually went back five or six years. Jeremy Isaacs [who was then the chief executive of Channel 4] had seen Down and Out, and said, ‘We’ll have ten of those by our first week of transmission.’ We did five, and were a year late in delivering them. Those films got us into commercials, and there was quite a delay in getting another five out. We were so busy. We didn’t mean it to drift for as long as it did — it just did. Because we were being offered three-course meals four times a day by the ad agencies.

Richard ‘Golly’ Starzak: When you were shooting, it wasn’t in your interest to stop and come back the next day, because something would have moved, and you wouldn’t be aware until you got to the end of the shot. Quite often, we were there all night.

Peter Lord: At the end of War Story, there’s a scene where his wife and her mother are frantically knitting socks for the war effort. Then he comes in, tells them there’s a blitz, grabs the dog and exits. The camera pans off them and up into blackness to land on him as an old man, talking. That was all done as one piece, which is ludicrous, because now it would be so easy to do it as some sort of effect. Nick [Park] was helping me — we were animating together. It was ridiculously late at night, and I remember lying down on a piece of polystyrene as a bed for about five minutes, while Nick was doing his bit of animation.

David: We were shooting on film, and we’d send our film off to Technicolor. We didn’t want our shot to be [processed] on separate days, as the chemicals in the bath would be very slightly different; the negative would be developed in a very slightly different way — it was just about visible. So that’s why you always wanted to finish your shot [overnight].

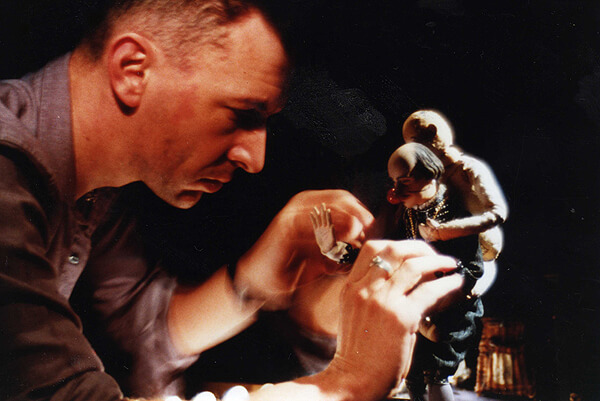

Barry Purves: I had a definite schedule, and you all laughed at me. I think I shot Next in five and a half weeks.

Peter: You were admirably fast and efficient.

Barry: On Wind in the Willows, we didn’t have video assist and we were shooting on 16mm. Our schedule was 23 seconds a day! That’s good training.

Golly: I think my shoot was really quick. I wish I’d taken a bit more time, now! I wanted Ident to look kind of rough, boiling. But I landed in the middle: it wasn’t nicely animated and it wasn’t boiling.

It has a punky, anarchic feel.

Golly: I was a punk, yeah. I wasn’t sure how the characters were going to animate, because they didn’t have any legs — they were just tall phallic things. [I had a steel block made] with a ratchet and winder, so I had this heavy weight I could move around easily, and just wind the characters up and down.

David: Paul Madden had commissioned the first five [Conversation Pieces], but he was very hands-off. He was happy to have [another] five five-minute films, so we really had quite a free hand on them. We showed him a sheet for Creature Comforts, which had six pictures of animals on it, and said, ‘It’s about animals in a zoo.’ Animation wasn’t costing the channel a lot of money.

Barry: But it was a decent budget. Next cost £50,000. I’d kill for that budget now!

Making Next (image courtesy of Barry Purves)

David: And also, they said, ‘Here’s a decent budget — keep some of it back for your next project. We want you to do more.’ There was a great sense of hope.

Peter: We sat around, us four and Nick Park, and chucked ideas around to try to link the films thematically. The original title for the series was Armature Theatre.

Golly: We decided that ‘armature’ didn’t mean anything!

Peter: We discussed the series being about ‘men’s things’ — I don’t know what those would be, precisely! Issues of masculinity. We briefly had an image that the films were going to be tightly grouped in some way. And then that clearly wasn’t going to happen, so thereafter we each worked pretty much on our own.

David and Peter, you’d been to the Zagreb festival with your earlier film Down and Out. You’ve written about how you were suddenly exposed to this world of adult animation. Did that experience change the way you approached filmmaking?

David: I think it did. I remember seeing what I thought was a straight Eastern European film there, but which was actually Nocturna Artificialia by the Quay Brothers. I thought, ‘Blimey, it’s the BFI!’ You could see national trends: the Italian stuff was basically sexual innuendo, men’s fantasies. You just never saw this stuff in the UK at all!

Peter Lord and David Sproxton’s Down and Out (1977), made for the short film series Animated Conversations that served as a forerunner to Lip Synch

By the time you made Lip Synch, Channel 4 had been broadcasting stuff like this for a while. Had that further influenced you?

Peter: It probably had. We’d seen more artists’ voices.

Golly: I think festivals really did that for me. Annecy, Stuttgart…

Barry: You and I went to Hiroshima, Golly.

Golly: I’d taken a bottle of whisky as a gift to a Japanese person, but it broke in my bag and soaked into all my clothes. I smelled like a distillery.

Was Lip Synch a self-conscious attempt to create something for adults, or were you just making what you wanted, and for which there now happened to be a platform?

Peter: Both at the same time. It goes back to Down and Out, when we first picked up the idea. To this day, I expect, people on the streets of Bristol would say, ‘Of course, animation is for kids.’ But we never felt that way, I don’t think.

Golly: I’ve just thought of another big influence on me: Dimensions of Dialogue by Jan Svankmajer. That’s a conversation, so there’s quite a lot of it [in Ident]. You’d never seen [films like that] before. When I was in college, Down and Out blew my mind as well.

Barry: Channel 4’s thinking was to do things that hadn’t been done before. A for Autism came out, which was a remarkable film. And Erica Russell’s Feet of Song, which was beautiful. And Joanna Quinn. But at the same time, the BBC were doing The Animated Shakespeare.

David: The BBC wanted to jump on the bandwagon, so they sent their animation unit to Bristol. In fact, A Grand Day Out first went out on Channel 4, but The Wrong Trousers was on the BBC. Suddenly you had this not-quite-rivalry, but you had both channels…

Aardman’s original studio at Wetherell Place

Next and Ident are the only films in the series with music.

Barry: We plotted the music first. It was very mathematical. I worked with Stuart Gordon, and we came up with 35 variations of the same eight-beat phrase, with a strong beat on the seventh. So when I did the storyboard, I knew I had seven gestures to tell Romeo and Juliet or whatever. People still love the music.

Golly: It was such an earworm. I remember not being able to not hear it. I’m glad it’s stopped, though!

Barry: Because our sets were that close. We tried to play the music when we were filming, to get the gesture. But unfortunately everybody else was about two feet away, listening to it 250 times a day.

Golly: With Ident, I wouldn’t call it music! We were trying to do a soundscape — it was with Stuart as well. Actually, to me, it sounds very crude now. I honestly can’t even remember recording it. I remember it being fun, because we were just picking things up, like, ‘What does this sound like?’

Barry: We had good air raid sirens in War Story.

Aardman’s early years were marked by experimentation. By the time you made Lip Synch, were you conscious of having a brand?

Peter: A bit. What we’d become known for from Conversation Pieces was realism, naturalism.

Golly: That’s what I regarded Aardman as when I joined. That was the brand.

Peter: Then Nick changed it all with Creature Comforts and Wallace and Gromit, obviously. But we had a clear identity. That same period, when we were doing commercials, we were very popular. And, you know, Barry was animating bras and things like that. It wasn’t all naturalism at all. We started from that point, and then proved to be very good at puppet animation. If you wanted something apparently three-dimensional to move expressively, we were the go-to guys.

David: As Pete says, then Creature Comforts came out, [and we ended up doing lots of commercials with talking animals]. We ended up becoming very typecast. But we didn’t have that much competition.

Barry: What I love about War Story and Creature Comforts is that the audio and the visuals are sometimes in conflict with each other. What he’s remembering isn’t what [you’re seeing].

David: And that’s the joy of the vox pop. You can take this very raw unscripted material and create something completely different. And I think part of what we learned when we listened to these tracks is that most conversation is tedious and dull and repetitive.

Golly: There are so many mistakes in syntax and grammar. When you’re having the conversation, your brain wipes that away, but when you listen back to it, it’s quite bizarre.

David: When you read [the transcripts of the recordings, they] often made no sense whatsoever.

This has been a fascinating conversation. I’m going to take it away and animate it. Tell me what animals you want to be!

For more on Aardman check out our 25th Lip Synch anniversary interview with Nick Park and Peter Lord as well as our Skwigly archives and find the studio online at aardman.com