Interview: Jordan Canning & Howie Shia discuss NFB collaboration ‘4 North A’

Having built a solid reputation as an award-winning director whose work includes the feature films We Were Wolves, Suck It Up and (with Kris Booth and Renuka Jeyapalan) Ordinary Days as well as over a dozen shorts, Jordan Canning has more recently collaborated with the National Film Board of Canada on her first animated outing 4 North A.

For this project Jordan, a graduate of the Directors’ Lab at the Canadian Film Centre whose other work includes directing for television series including This Hour Has 22 Minutes and Schitt’s Creek, paired up with animation director Howie Shia, whose own filmography includes the NFB productions Ice Ages (produced as part of the their Hothouse apprenticeship scheme), Flutter, Peggy Baker: Four Phrases and BAM, as well as Marco’s Oriental Noodles for CBC and a variety of creative endeavours as PPF House alongside his brothers Tim and Leo.

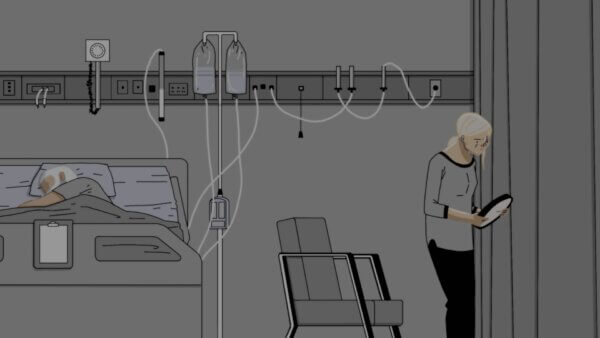

A woman sits in a hospital room, alone with her dying father. As the constant din of antiseptic hospital noises pushes her to confront her inevitable loss, she escapes into a series of lush childhood memories.

Told with a quiet, expressive soundtrack and beautiful, subdued design that shifts between the pale hospital palette and the impressionistic landscapes of the woman’s memories, 4 North A is both a tender celebration of the fleeting joys of life and a bittersweet reminder that we don’t always get the closure we seek.

Having recently premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, 4 North A this week sees itself as part of the Ottawa International Animation Festival’s line-up.

Jordan, your background is in (primarily) live-action shorts and, more recently, features and television. What drew you to animation for this project?

Jordan Canning: This film is an amalgamation of several initially disconnected ideas I had percolating in my head for years. I had a little collection of stories that my mother had told me about her childhood, spending summers in rural Ontario, and there always seemed to be a through line of animals and death. I knew that I wanted to turn them into something, but live action never felt like the appropriate medium. I worried they might come across as saccharine, or that I wouldn’t be able to properly convey them visually. Years later, I was working with the NFB, giving script notes on a short film collaboration between a live-action screenwriter and an animator. I didn’t know that this was something the NFB did, that it would even be a possibility to tell the story through animation. But once I started thinking about it, it was the only thing that made sense.

While the film is ostensibly presented as fiction it seems to carry a distinct personal resonance. Are there elements of it that are rooted in your own experience?

JC: I always felt there was a way to connect these animal stories to my mother’s experience of being at her father’s hospital bedside as he lay dying. An examination of how a parent must try to teach a child about death—to learn to accept it as a natural part of life—but how we are never fully prepared when it finally comes. It ended up evolving into an even more personal story, though. When I wrote it, I was caring for a loved one who was very sick and had been spending a lot of time in hospitals. They can be such isolating places. You can be surrounded by people but feel so lonely. I began to imagine this fantasy, that my mother and I could have somehow crossed paths during these extremely painful times in our lives. That we could have found each other, even for a moment, and provided some comfort and connection.

From the initial germ of the idea of the film what was its journey as far as getting made, and what brought you and the NFB together for it?

JC: I sent the script to NFB producer Annette Clarke, and she agreed to come on board. We began discussing animation styles and trying to narrow down a list of potential collaborators. At some point, another NFB producer, Jon Montes, suggested Howie Shia. I watched his work and was so struck by his deceptively simple ways of rendering emotion. Howie read the script and, luckily for us, it spoke to him. We began working together, at a distance (I was in St. John’s and he was in Toronto), and sending images and sketches back and forth. Mostly, we spoke about how to convey the experience of waiting in a hospital, and how to delineate between the suffocating, sterile present-day environment and the lush memories she escapes into. Because of life circumstances, there were times when either he or I would need to take a pause from the project. Ultimately, I think this made it so much stronger, as we could come back to it a few months later with fresh eyes and a clarity on what could be stripped away or what needed more work. We were very fortunate that the NFB gave us the time and space we needed to develop it properly.

4 North A (National Film Board of Canada)

Do you expect animation will have a role to play in future projects of yours?

JC: I would like to hope so! This was honestly such an amazing experience, and a wonderful, organic collaboration. My imagination has been opened to the boundless possibilities of animation; I’m excited to see what kind of stories it cooks up without the restrictions of live action.

Howie, we last caught up with you when you made the short Marco’s Oriental Noodles for CBC, can you tell us a bit about what you’ve been up to between that project and 4 North A?

Howie Shia: ‘Fallow periods’ for me mostly just involve running around trying to keep my kids fed and clothed. I do work in the evenings after everyone is asleep, and I think that during the time between Marco’s and 4 North A I was working on a few things: a children’s book, a graphic novel, and scripts for a series of shorts set in the same world as Marco’s. I’m trying to work on paper as much as possible these days—both with writing and drawing. Less distraction and less forgiving. Also, I read a lot. I think people don’t talk about that as part of their practice, but I don’t think I could produce work if I wasn’t reading.

Were there any new approaches you adopted when taking on this project as far as the visuals were concerned?

HS: The film kind of organically evolved into a mix of Jordan’s live-action instincts for camera movement and coverage—subtle little pushes and pulls and shifts and added coverage that I wouldn’t necessarily have known to do—contrasted against moments of very controlled, almost schematic, graphics to convey the kind of mental map-making that one has to do when navigating the house-of-mirrors-like corridors of a hospital. And then all of that was contrasted against the messiness of the memories which, because they were memories, could do a lot of expressionistic jump-cutting instead of adhering to traditional coverage. That said, I think we were also careful to not go so loose in the coverage that we would spill out into “dream-state” editing, which is a different thing altogether.

4 North A (National Film Board of Canada)

The aesthetic sensibilities of the flashback sequences – in particular the colour palette – against the present-day scenes make for a very effective juxtaposition. Was there much by way of experimentation when it came to the visual development?

HS: Designing this film took a lot more effort than I’ve put in in the past—not in terms of labour but in terms of thinking. We really wanted to contrast the sterility of the hospital with the flesh of its patients, and then contrast all of that with the impressionistic smudginess of the memories. In fact, it wasn’t until I saw a show of Egon Schiele drawings at the Met Breuer that the whole dynamic really unlocked for me—something about the sensuality of the drawings, especially the smudges of blue in the flesh tones, rebelling against the starkness of the gallery. In the end, a lot of the decision making for both the hospital and memory scenes came down to the strict parameters we put around the drawings themselves: controlling the line weight and levels of precision, finessing the colour palette, playing with frame rate, etc., and pairing those correctly with the shot composition and editing style we were developing.

Had you been familiar with one another’s work before coming together on this project?

HS: I had seen some of Jordan’s shorts without realising they were by her. I’d known her primarily as a director of comedies, so when she sent me the script, there was a brief moment of confusion as I couldn’t figure out where the jokes were.

JC: I wasn’t familiar with Howie’s work, no. I wasn’t really familiar with very much animation at all, to be honest. Working with Howie and the NFB has certainly changed that, and it’s been a real pleasure “catching up” on the incredible wealth of creative work that’s out there.

Was working together an offshoot of the NFB’s role in the film’s production or had that been the plan from the start?

JC: The NFB was instrumental in bringing Howie and me together. Without their help, I honestly wouldn’t have had any clue where to begin. It was a very interesting process, trying to figure out what style of animation I pictured for the story. It was a language I wasn’t adept in, so it really was sort of trial and error. I was watching a lot of shorts, taking in the styles. Yes, I like this; no, definitely not like this. When I saw Howie’s work, everything just clicked into place.

4 North A (National Film Board of Canada)

Can you break down your working dynamic as regards the film’s production pipeline?

HS: My involvement was built up gradually and it’s mostly thanks to Jordan’s creative and professional generosity that I came to take on as much of a role as I did. We started mostly with just my sending her drawings and her commenting on them. Eventually those drawings became an animatic, and from there we would go back and forth the same way, but this time about edits.

JC: What Howie refers to as my generosity I think of more as just recognizing my good fortune to have him as a partner, and knowing that his ideas were only going to make the film so much better. I’m eternally grateful for this collaboration, and sometimes a little stunned at how easy it felt the entire time—despite distance, long periods of down time, life getting in the way. It was always a pleasure to return to the project and pick up where we left off.

HS: The nuts and bolts pipeline for the actual animation was very straightforward: I would set up shots in TVPaint and send them to our incredible animators (Miranda Quesnel, Simon Cottee, and Duncan Major) to bring to life. I didn’t do too much in terms of key frames because we really wanted to treat the animators as actors. So Jordan and I tried to talk the emotional arc of the scenes through with them instead of obsess over blocking. One great gift we had that I think is a rarity—especially for productions this size—is the permission and consequent scheduling/budget from our producers (Annette Clarke and Michael Fukushima) to ask our animators to do multiple rough takes for the key shots where the acting would really be the only lever we had in controlling the layering of emotions and story. I think Annette and Michael both understood what we were after and had the foresight to build an infrastructure around the film that allowed us to find the film as it was being made.

This has obviously been a disruptive time for everyone, did the current pandemic situation impact production at all?

HS: Ha ha. No, we actually finished production before the pandemic, but also, the whole thing was done remotely, so it wouldn’t have changed anything. Miranda was in Germany; Simon, Michael, and Sacha Radcliffe (sound designer) were in Montreal; Duncan and Annette were in St. John’s; Jordan was splitting her time between various locations across Canada; and Jennifer Krick (clean up and colour) and I were in Toronto. One great thing we did do, though—which would not have been nearly as effective over ZOOM—was to have a kick-off meeting here in Toronto where all of the animators came in to talk the film through, including an incredible (and hilarious) hands-on TVPaint tutorial by Simon. Again, this is credit to Annette and Michael, who understood what something like that does for establishing the tone and trajectory of a project. As I get older, I think I’m finding that those soft insights from a producer are really among the most important supports they can offer. On top of everything else, they make their story notes much easier to take because you already know that they’re trying to make your movie and not someone else’s.

4 North A (National Film Board of Canada)

The film will be screening at Ottawa shortly, is this an event either of you have been involved with before?

HS: I had an early film about the great dancer Peggy Baker play there many years ago, but beyond that I’ve always only taken part as an enthusiastic audience member. It’s a very special festival in that, given its size and prestige, it still feels very much like a festival on the lookout for independent artists and hidden gems—without having to pit them in battle against the mainstream.

JC: I have never been, no. But am very much looking forward to consuming as many films as I possibly can while still wearing pyjamas.

What are you working on presently/next?

HS: I was lucky enough to receive a grant from the Canada Council to finish my kids’ book, so I’m busy working on that right now. In the new year I will be helping out on an exciting new adult animation project at Netflix. Beyond that, I’m still writing and reading and trying to raise my kids.

JC: I have a feature film that I’m working on and am developing a TV show in between directing some episodes of television. Mostly, I’m excited to get back to Newfoundland at Christmas and finally see all my family.

4 North A screens as part of OIAF‘s Short Competition 8 screening which streams live September 30th 7pm EST and will be available in On Demand October 3rd-4th.