25 Years of the McLaren Award 1990-1994

2014 is quite a momentous year for the Edinburgh International Film Festival as it hosts a series of events continuing the centenary celebrations of auteur filmmaker Norman McLaren – McLaren 2014. This year sees the award bearing his name being handed out to its 25th recipient. As you may expect from an award named after an experimental filmmaker the selection of winning films offers a varied display of craft, storytelling and execution all in the name of animation. Many of the earlier films have slipped into the unknown whilst their contemporaries continue to be well known which, in some respects this mirrors the common perception of Norman McLaren himself, innovative yet unknown. With this in mind Skwigly have called upon writers and guests to review past winners of the award and give you the chance to revisit these innovative gems of the past in a series of articles starting here with 1990 to 1994.

Whilst the film has somewhat disappeared into the ages whilst other films in its category, heavy with Aardman favourites such as Nick Parks Creature Comforts and Peter Lords War Story remain in the public consciousness it perfectly encapsulates what the McLaren award is about, This is a prize awarded not to the overly commercial but to the accessible that use an avant-garde approach to style but retain a character and appeal that pleases the audience, something which future McLaren award winners would have in common.

The hustle and bustle of big events, the social scale and the thrill of horse racing are nicely documented in Susan Loughlins NFTS film Grand National. This film displays the peculiar skill, familiar in all the best animation and that is to engage an audience with a subject matter they may not be over familiar with or indeed interested in. I’m not a big horse racing fan, the sight of John McCririck turns my stomach, but the ceremony of the event is captured in a way I had never been inclined to consider before. The Grand National rolls into town like the circus bringing with it a festival of colour and characters that lead to the drama of the race itself which is highlighted by a careful selection of bold and bright colours. The illustrative style used in the piece is loose yet its representations are easy to interpret with brushstrokes that tentatively display the equine anatomy without looking amateurish that also fit the pace of the film whether during the frantic flurry of motion during the race which offer a spontaneous motion that carries the audience along as if the race were live.

Whilst the film has somewhat disappeared into the ages whilst other films in its category, heavy with Aardman favourites such as Nick Parks Creature Comforts and Peter Lords War Story remain in the public consciousness it perfectly encapsulates what the McLaren award is about, This is a prize awarded not to the overly commercial but to the accessible that use an avant-garde approach to style but retain a character and appeal that pleases the audience, something which future McLaren award winners would have in common.

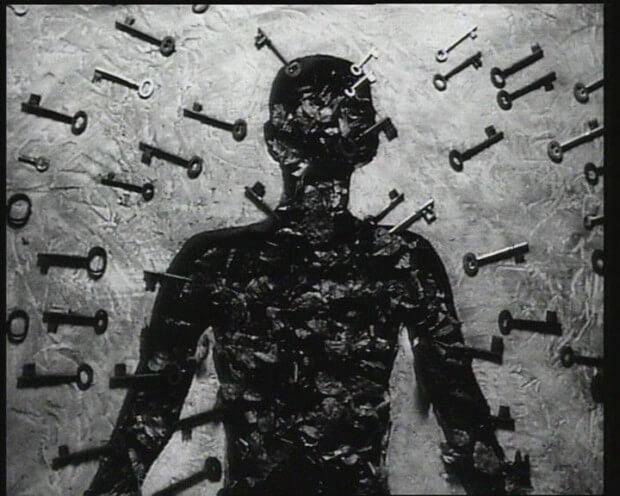

David Anderson’s film opens on a globe of doors – a world of opportunities. As the viewer is trailed though door after door, opening into worlds, scenarios with dream like qualities. With a mixture of experimental film making techniques and pixilation the film tracks the imagined conversation between a man and a woman as they discuss a key to the end of the world. Reminiscent in style to the work of surrealist film makers such as Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí creating an uncomfortable world of illusion where the inanimate live and create a dream like labyrinth of cut up photography and locked doors.

The cinematography and look of the film lends itself to the photography of Man Ray and is contextualized by the stream of conscious narrative (often used for inspiration in surrealist work), with its disjointed rambling style of writing, the piece is written and narrated by Russell Hoban himself. The story continues from Hoban’s book ‘Ridley Walker’ in which he discusses a post apocalyptic world in which someone has pushed the button or indeed ‘turned the key’. Created in 1991 Door is the second film from the Deadtime Stories For Big Folk series, the film itself is more reminiscent in theme and mood to some 80’s production such as Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice or Paul Berry’s The Sandman in terms of creating a nightmarish ambience. On a broader note the film is like an open discussion with the audience to consider the symbolism behind a closed door and how humans eternally search for the right ‘key’ to questions which is part of our need for knowledge and understanding of the world, and how in turn it may lead to our ultimate destruction. The previous episode from the series entitled Deadsy won the special jury prize the previous year in the same category at EIFF. The film is a great example of the legacy of the eccentricity and avant-garde art that lies at the heart of much of the British art produced today.

Films tackling sensitive subject matters will always provoke attention and this is positively so in Tim Webb’s A is for Autism. Being 4 years old when it was released I can comfortably say that this film passed me by, but when learning more about the McLaren Award and all it’s many winners A is for Autism stuck out to me as one to devote my attention to. Autism is a topic that has been talked about for many years, with countless films and documentaries on the subject, however Tim Webb was among the first to use animation. Every drawing, voice, story and musical number within the film was all produced or based on creative work from a selection of autistic children. This uncomfortable world, in which autism takes many forms, is represented here with the fast paced, quick cutting and mesmerising selection of animation and live action.

As a viewer we are taken through a journey of life as a child living with autism, from the vast open playground to the hidden sanctuaries within their minds. Animations based on the children’s illustrations blend and morph into one another creating a kaleidoscope of varying styles and interpretations of the world they live in. Their voices help us to imagine life in their shoes and help explain, at times, some of their surreal illustrations. From 2D worlds we are thrust into stop-motion which brings us closer to the realities of what is being dealt with. This constant link up between animation and live action really help to remind the viewer that this is real and all these feelings have been felt and experienced. The films creativity reaches new highs when we find out that some of the animation has been produced by a child who’s skill in animation is quite frankly, overwhelming. Frame by frame he draws trains, journeying through imaginary landscapes, speeding past other trains, entering and exiting through tunnels. As it does so the camera twists and turns revealing every angle with pin sharp precision. A is for Autism was researched for a year before production making this a truly comprehensive look into a child’s autistic world and one that will stand for a long time to come. It is a real and personal journey into the minds and feelings of autistic children, we’re not just imagining how it feels, but are somehow transported there, through the minds of those children.

I first saw this film in 1995 when Bob Godfrey brought it along to Southampton Institute to show the students. At the time I think I found it baffling and grotesque, but I like it a little better every time I see it. The visual style is perfectly suited to the garish world of the travelling funfair in which it is set. Ged Haney spent several years creating this film and the work shows in every frame. The technique is traditional cel but the style is unconventional, somewhere between old-school Beano and Dandy comics and the paintings of Rousseau, giving the carnival setting that same sinister, menacing aspect that has been tapped into by Stephen King and The League of Gentlemen. Here, though, there are no murderous clowns or wife-stealing blackface minstrels, only the horror of being trapped in a life not of your choosing.

The story is about a pair of Siamese twins who perform a song and dance routine at the funfair, but privately dream of how their lives might have been as two separate people, one as a footballer, the other as a pop star. Wandering through a hall of mirrors they almost literally tear themselves apart in frustration at their fate, but then present their cheerful public face to their audience – who go away heartened and warmed by the brothers’ performance. The closing shot is a lingering, poignant closeup of the twins’ faces as their smiles slowly melt away, quietly but starkly revealing the hidden darkness below the colourful surface.

Mulloy’s dark wit smacks you in the face, spits on you, then stabs you in the chest repeatedly in his McLaren award winning short The Sound of Music all the way from 1992. Sort of customary of his work, there’s something about its relentlessness that I can’t help myself enjoying for some reason. It’s a bold, frightening and strangely funny observation of a greedy and decadent society. There’s something about the sparseness of his work as a whole that I admire. A few crudely drawn elements with coarse movement plays with the brutality and ugliness of his story. I often ramble about why things are animated, particularly in a time where animation is heavily saturated and processes are standardized, but this film is testament to matching its form with its dark subject matter. It’s pretty violent stuff, but I can’t help but take pleasure in its unpolished appearance.

There’s also something about the pace of ‘The Sound of Music’ that jumps out at you. It’s like we’re dragged along at 100mph and left in a gutter at the end, as it spirals into streams of consciousness between ugly scenarios. I like it, but it’s horrible. I think that it’s an important film, not necessarily in a singular way, but in its maker as an artist. I’m drawn to work led by a voice that doesn’t compromise their vision to fit in with the norm. Mulloy certainly doesn’t do this, and that’s why his work stands out and screams from the crowd.

25 Years Of The Mclaren Award Articles