20 Years of LIAF + Interview with Nag Vladermersky, Festival Director

In its 20th year of existence, the London International Animation Festival has grown into a well-loved and well-trodden path for animated filmmakers. The 10-day event screens films across the city, inviting audiences into subversive lands, telling tales of the untold and debuting first-time filmmakers. LIAF has continued to create an environment encouraging animation from an independent perspective. The festival supports the kind of filmmaking which isn’t afraid to go a little deeper, to get a little stranger (and does it all again next year too.)

This approach to film programming, or what Nag Vladermersky, the festivals founder, calls a ‘D0-It-Yourself ethic’, creates a setting which welcomes the emerging filmmaker with open arms, and perhaps encourages the prospective one to keep making unique films. About 20 years ago, Nag and a small team started to put on events in London at venues such as The Rupert Street Cinema (now defunct) and the Curzon Soho. We caught up with Nag, LIAF’s long standing director, to find out more about his work with the festival.

At its 20th anniversary, LIAF has grown tremendously, from small beginnings to an international 10-day festival. Can you speak to some of the challenges of building the festival and keeping it going all these years?

The obvious (and very boring) challenge is money. Firstly, I do want to acknowledge the continuing support of our two main funders over several years – the Arts Council and Film London, without their support we would never have made it to 20 years old. Even though we are an established festival, very soon after each LIAF ends the first thing we have to do is think about our funding applications for the next year. It would be so much easier for us if could apply for continuous funding for several years rather than re-invent the wheel each year. But I can’t complain too much because, as noted, we have been lucky enough to be fairly consistently funded. It’s just that it takes a couple of months of work at the start of each year writing funding applications when that time could be spent doing more programming and planning – which is obviously the fun part of running a festival!

Also, it may seem weird to complain about but as we have grown and become more established we now receive so many more film entries year-on-year but the standard hasn’t necessarily got higher – it means we have much more content to sift through to make our decisions about what to screen. It has got to the stage where the first 6 months of our year are centered around watching thousands of films, databasing, programming, culling, and making the final decisions.

I think the main reason we have managed to build the festival slowly but surely over all these years is because we have remained a very small team. For 12 of those 20 years, essentially 3 of us have come together to remain consistent in our programming, without losing overall quality and managing to remain humble.

Over that time, we have developed pretty foolproof systems that work well for us. It’s easier when you don’t need a consensus on how to do something by going to a board for instance. Bureaucracy can weigh you down. So we do fly by the seat of our pants sometimes and there are many occasions, especially in the final couple of months of run-up, that we have to problem-solve and very quickly – but we always manage to get through.

Having said that – we do take on interns and volunteers running up to and during the festival. As the festival has got bigger our workload has increased enormously and I do sometimes think that 1 or 2 other workers to help share the load would probably mean we aren’t working ridiculous hours in the second half of the year! It’s not very good for my work/life balance but at the end of the day we absolutely love what we do, we love the artform and being able to present these amazing films makes it all hugely worthwhile. The biggest buzz of our year is the 10 days when the festival is running.

Do you think your previous experience in making independent animation films has influenced the way you programme events for LIAF?

It probably has. I’ve always had a DIY attitude towards art – whether it’s music or film. I started off playing in various bands when I was in my 20’s and set up and ran my own record-label. It was a great way to spend your 20’s! Then when I started making short, animated films a few years later I had a similar attitude. The thing I love about animation is that you are in total control, you don’t have to bow down to actors or other crew members – essentially, it’s all down to you and I carried over that DIY attitude towards my own filmmaking. I sort of fell into running animation events in a similar way. I just decided to give it a go. And over the years I feel blessed that I have met so many amazing animators from all over the world, many of whom I would now consider to be good friends, who share a similar attitude towards independent filmmaking.

What do you find most rewarding about your work?

Probably the above – being able to meet so many talented animators and filmmakers and others connected to the industry. The world of independent animation is quite a small one in the grand scheme of things, and as you get to travel around the world to various festivals you tend to bump into the same people. But there are also so many new and talented animators coming up through the ranks all the time.

It’s also very rewarding to feel that our audience is an enormous part of why we do this and that they can contribute – for instance, we have had audience voting from the very first edition and this really helps us to shape future editions of LIAF by knowing what they’d like to see more of. And the lovely comments (in general) that we get back on the zillions of bits of paper are very humbling to read.

How might the festival take shape in the coming years? Could you share any ambitions for future editions?

There is still room for growth we believe – and Mandy (LIAF Producer) is really the one to talk to about that – she’s the brains behind running LIAF! Since COVID and gravitating towards being a hybrid festival – running online streaming as well as in-cinema screenings – we have increased our audience and this year it has really started to pay off with a much bigger worldwide audience. We really want to hang on to a local and loyal audience and one that to a large extent has been with us since the start of this journey 20 years ago. We’re in this together! But the potential to increase our audience worldwide with streaming capabilities is enormous and I think that’s an area we’ll be looking at over the next few years.

Another area that we are growing and developing for LIAF is putting on more diverse screenings – such as our Figures in Focus programme (curated by Abigail Addison from Animate Projects) These films give voice to female and non-binary filmmakers. Then there’s our Disrupting the Narrative programme (co-curated by Osbert Parker) which presents films by Black and Ethnic Minority filmmakers. That’s something we want to do more of at future festivals.

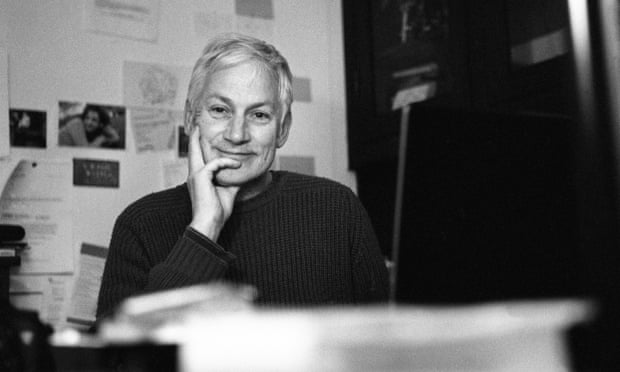

LIAF 2023: A tribute to Paul Bush

At the opening gala for LIAF 2023 a handful of secretly selected films were screened at the Barbican, considered to be the ‘cream of the crop’ of this year’s competition entries. Following this was an in-depth look at the films of Paul Bush. Paul was known to many as a maestro of moving image. His passing earlier this year in a motorcycle accident has led to a resurgence and celebration of his work. Paul’s utter devotion and obsession with animation as a form came across in the films which were screened back-to-back in the programme.

For a first-time spectator of his work, one might notice an arc of playfulness or mischief played out in the films when watched chronologically. In the early 1990s Bush experimented by engraving directly into the surface of 35mm colour film stock with films like ‘His Comedy’ and ‘Still Life with Small Cup’. He grapples with the classics in ‘His Comedy’, a reimagining of Dante’s Divine Comedy. This film is tonally dark; morality, heaven and hell are characterized by the light and dark contrasts achieved with a scratch on film technique.

In Paul’s later work, however, he moves into an ever more playful, philosophical territory. In ‘Furniture Poetry’ and ‘The Five Minute Museum’, he explores object replacement animation in its propensity to be delightful and absurd. Paul became known for this single frame technique which had the ability to incite the impossible, a museum of man-made objects viewable in five minutes, a room containing an infinite number of interchangeable chairs.

Paul Bush (Photograph: Lewis Bush, Source: The Guardian)

Around this time, he also decided to offer his audiences a disambiguation. In ‘Paul Bush talks’, accompanying the film ‘While Darwin Sleeps’ Paul begins to address the audience himself, accompanying his short films with a commentary in which he speaks directly to camera. He repeats this process in ‘Stupid Soliloquy’ where he speaks to the making of ‘The Five Minute Museum’. In an amusing vignette of Paul’s character, he appears to spin with the camera in his hands, getting faster and faster, whilst still maintaining his dialogue. Paul speaks of Pushkin and how he had said that all poetry should be stupid. He wishes to invite stupidity into the act of filmmaking too… and that’s when he gets so dizzy that he falls over.

There is something very heartening about Paul Bush’s resignation into silliness. ‘Stupid Soliloquy’ is a record of his thought process and also a testament to his good nature. There is a sense of him dancing with these greater philosophical ideas whilst also paying heed to the absurd, of not taking himself too seriously.

Warmth and admiration for Paul were echoed through the panel discussion which followed. Amongst these speakers was his wife, fellow animation tutor Robert Bradbrook and a few more film making peers. Together they shared anecdotes from Paul’s life which were both nuanced and bittersweet.

LIAF 2023: Highlights & Must-See Films

Elsewhere at the festival, a selection of the best student films were collated into ‘The Best of the Next’ in the dark basement setting of the Horse Hospital. 26 films were chosen in total and spread over two screenings. These films were marked by their bold voices, eclectic use of technique and vivid imagery. Amongst those which stuck out were the exquisite drawing style of ‘Funeral at Nine, a Gobelins grad film directed by Mamadou Barry, Rodrigo Veras, Ziyu Wang, Junhao Xiang, Wang Yu, and Linfeng Zhou.

Funeral at Nine by Mamadou Barry (Source – Gobelins)

At the funeral of the gardener, three brothers pause for thought and become lost in dream-memory. The youngest has a peculiar vision upon looking into his jar of his captured butterfly. The landscape transforms and shifts perspective, figures are distorted as they travel across the screen in a hall of mirrors style. The late gardener lies sleeping inside of a humungous flower. The butterfly feeds upon his corpse in a seemingly symbiotic nature and the boy learns something about the circle of life.

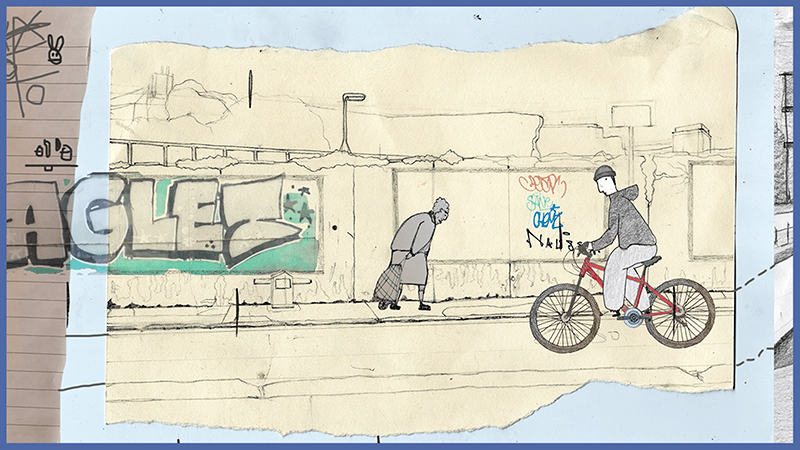

The Unchaotic Cabinet which wishes for me to sleep

In ‘The Unchaotic Cabinet that wishes for me to Sleep’, we follow a young man named Laurence Snell on a bicycle, traversing through suburban Dublin and into town. This journey sees him lost in his own thoughts, thoughts which spring up at a natural pace and which seem to overlap one another in a fragmented and psychedelic ramble through Dublin. The cyclist reflects upon his state of mind along the journey. This stream of consciousness style is akin to a kind of surrealist automatism. Each new scenario resembles the page of a sketchbook, a scribbling, a half-formed thought.

The director of this short, Cilll G, is mindful of his artistic influences, listing comic artist Chris Ware and a handful of poets: James Joyce, WB Yeats and Patrick Kavanagh’s ‘Dark Ireland.’ had made an impact on the film. These influences seem to be at the tip of his proverbial tongue whilst animating. Laurence is cycling in a liminal realm, close to the subconscious, it is a place where the words of poets are ripe, they are alive in him, and not yet fully cemented into adolescent consciousness.

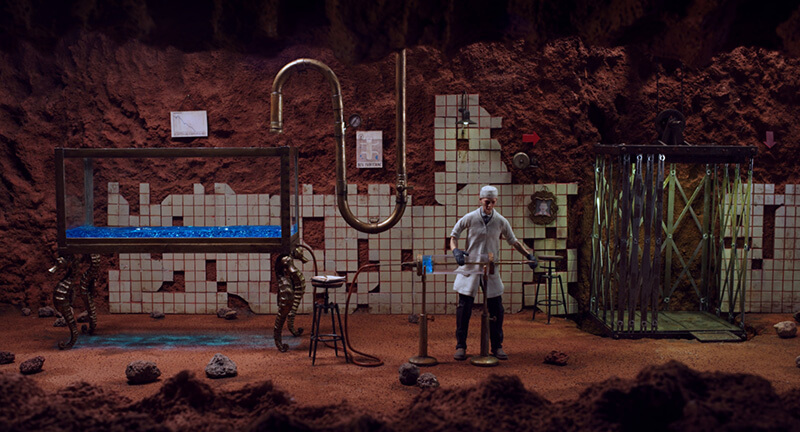

Perhaps the pearl of this year’s festival, was the Long Shorts Competition programme, taking place at the Garden cinema, a cosy, art deco style independent which opened in Holborn last year. These shorts had longer runtimes and so they were able to draw audiences more intimately into their worlds. Subject matters were explored in depth, allowing the films to have more gravity. For Kaspar Jancis’ ‘Antipolis’, the subject was gravity itself.

Antipolis by Kaspar Jancis (Source – Nukufilm)

Jancis, known for his short films produced through Estonian studio Nukufilm, depicts a convincing microcosm of another civilization. The inhabitants of Antipolis believe the Earth to be flat, that is until a group of scientists build a machine to penetrate the arid crust of the desert. In a mission gone awry, explorers discover another civilization living on the other side of Antipolis. These two lands, it seems, exist simultaneously inside of a gigantic globe. However, existence in the other land proves difficult as the two peoples experience different poles of gravity. Upon entering the new world, they float up by their heels like helium balloons. This film seems to operate on a level of dream-logic. Although such marvelous imagery has come to be expected from directors like Jancis.