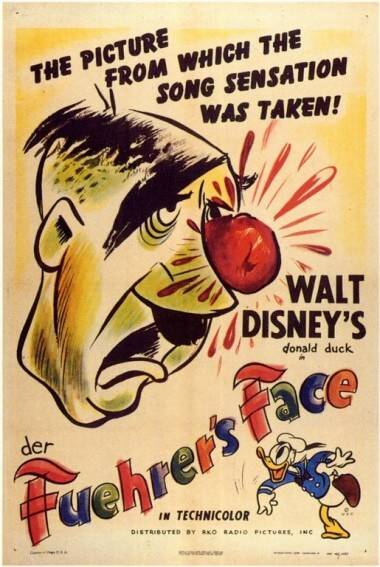

100 Greatest Animated Shorts / Der Fuehrer’s Face / Jack Kinney

USA / 1943

I was recently asked to contribute to a Walt Disney article a magazine was producing. Typing something up for this one evening my thirteen year old son approached and asked me what I was doing. “Walt Disney?” he replied when I told him, “He was friends with Hitler you know”

The idea that Disney was some racist or antisemitic Nazi has somehow penetrated the popular consciousness to such an extent that its almost accepted fact. And I’m not just saying this because of the daft utterances of a thirteen year old, just type it into google and witness the discussions where its treated as gospel by grown adults. Whether this comes from discredited books such as Marc Eliot’s Walt Disney: Hollywoods Dark Prince or from lazy Family Guy writers who apparently include knowing jibes about Disney being a racist in every mention of his name or just from urban mythology I don’t know, but like most conspiracy theories the whole argument pretty much collapses on any examination of any actual facts , historical documents or personal testimonies.

In direct contrast to the idea of supporting Hitler and the Nazis, during World War II, like many other animators and animation companies worldwide, the Disney Studios produced a number of anti-Nazi propaganda films for the US government in order to help the war effort and also to help the company survive this time of economic hardship. Although another motive was to try and recoup the losses suffered from Pinocchio and Fantasia, the profit margins that Disney charged on many of the government films were small or nonexistent as part of his contribution to the war effort.

Disney was contracted to make 32 propaganda, training, and educational shorts from 1941–1945; this kind of volume multiplied the studio’s usual output many times over and was achieved by producing the films in a simpler style. The best-known of these propaganda films was the Donald Duck short Der Fuehrer’s Face, winner of the 1943 Oscar for best animated short and one propaganda film that was produced to the full Disney quality of other Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse shorts.

Disney was contracted to make 32 propaganda, training, and educational shorts from 1941–1945; this kind of volume multiplied the studio’s usual output many times over and was achieved by producing the films in a simpler style. The best-known of these propaganda films was the Donald Duck short Der Fuehrer’s Face, winner of the 1943 Oscar for best animated short and one propaganda film that was produced to the full Disney quality of other Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse shorts.

In this satirical cartoon directed by Jack Kinney, Donald is a rather unwilling citizen of Hitler’s Germany, a totalitarian regime in which every surface and item is plastered with swastikas and images of Hitler’s face, each of which Donald is expected to salute, even when working an intensive 48-hour shift on a production line and a lot of the humor rests on the volatile duck’s increasing rage at the ridiculous and increasingly surreal demands put on him by the Nazi state. The film is a typical beautifully animated Donald short from this era, also featuring an excellently realised caricature idiotic marching band puffed up with mindless nationalism and annoying everyone with their pompous music and salutes. The title of the film was changed from Donald Duck in Nutzi Land in order to relate to a hit novelty tune “Der Fuerhers Face” by Spike Jones and his City Slickers, which voiced contempt toward the Nazi leader and his delusional master race egotism.

Other Disney wartime propaganda films included the distinctly non-Disney-sounding Education for Death; the Raising of a Nazi (1943), the story of how a German child called Hans is brainwashed from birth to be a good Nazi and a cold killer. The film is as strange as it sounds; its Disney stylings and gags are at odds with the rather disturbing subject matter and depictions of a sinister fascist state. Reason and Emotion (1943) is an interesting short with an adult psychological theme, again not something usually associated with Disney, concerning the struggle between our sense of reason and our emotions, and how Hitler used the rabble-rousing potential of the latter. This film is a good example of how these projects allowed the animators to experiment with different styles from the usual Disney house style; the characters here are often more caricatured, simplified and stylized, at times going toward the kind of designs that UPA would become known for in the 1950s.

Victory Through Air Power (1943) is a feature-length PR push for Major Alexander de Seversky’s proposal of more resources to be concentrated on building war planes. Disney felt strongly enough about this issue to devote his own resources to making the film. The realistic designs and the lovely 1940s-style special effects details recall the Fleischers’ popular Superman series. Reportedly, it was not until Franklin D. Roosevelt had watched Victory Through Air Power that he decided that the long-range bombing strategy would be part of the USA’s battle plan.

Similar to the way I have heard Der Fuehrer’s Face used by the hopelessly uninformed as evidence for Disney’s ‘Nazism’ (“Yeah and he made this Donald Duck cartoon where he salutes the swastika and stuff !”) the 1946 film Song of the South is used as evidence of Disney’s racism when in fact it had the opposite intention, if anything.

Now justifiably seen as tainted by its dated racial stereotyping, Song of the South presents several of the Uncle Remus stories from the books of Joel Chandler Harris. The animated stories are linked by scenes featuring live-action actors portraying Uncle Remus and two children. As Uncle Remus tells his stories, the film dissolves in and out of animation. Animation and live action would not be mixed together as successfully as this until Disney’s Mary Poppins in 1964 and yet Song of the South has never been released on video or DVD in the USA because of racial sensitivity to the portrayed image of the ‘happy slave’, although it has been re-released theatrically and released in all formats in other areas of the world.

We have to remember that his was a time when segregation between black and whites was absolutely normal and acceptable in public places, transport and schools in many southern states of the USA, with black people treated as second class citizens. In this way racism was not only common and acceptable at this time it was actually enshrined in law. Reflecting the attitudes of the era, some of the attitudes in Disney’s work could be seen as racist by today’s standards but than again so could any other work that reflected the attitudes of the era. You see these attitudes in many films and books from that time. In Song of the South Disney was making a genuine (if now seemingly-misguided) attempt to have a likable charismatic warm and funny African American central character in an era when this was extremely rare. If Uncle Remus is portrayed as uneducated and living in a wooden shack, unpalatable as it may be now, that was the second class reality many American blacks were forced to accept.

According to writer Neal Gabler in his book Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination (2006), in contrast to having racist intentions, Walt Disney was actually sensitive to the potential for racial stereotyping or “Uncle Tom” accusations in Song of the South and assigned Jewish left-wing writer Maurice Rapf to work on the script with southern writer Dalton Raymond. Disney hoped this would counteract any tendencies in that area, a detail of history which, along with providing more evidence that contradicts the image of his racism, also also shows a different perspective on the accusations of Disney’s antisemitism and intolerance of left wing views.

Note: The 100 greatest animated shorts is a list of opinions and not an order of value from best to worst. Click here to see all of the picks of the list so far. All suggestions, comments and outrage are welcome!