A Conversation with John Kricfalusi

There’s one week left to donate to John Kricfalusi’s first crowdfunding endeavour, the all-new standalone George Liquor short Cans Without Labels. Over the last month the Canadian-born animation legend responsible for The Ren & Stimpy Show and all manner of similarly manic cartoon lunacy has been drumming up support for his latest short from its own prospective audience. As of this writing over 2,500 supporters have stepped forward to help make the film a reality, incentivised by some of the most droolworthy rewards a crowdfunding campaign has offered to date. Skwigly was incredibly fortunate to have some time with Mr. K to discuss this latest venture, the body of work that came before it and the promising future of creator/audience relationships it could lead to.

© John K.

My Dad was completely against brand names, didn’t like to waste any money. There was a supermarket nearby that had a shelf at the back of the store where they sold damaged goods, and they’d mark the price way down. At the bottom of the shelf were all these cans that had no labels on them, all they had was a big fat marker that said ¢5 or ¢10, so you didn’t know what was in the cans. My Dad thought he could figure it out, he thought he was a can scientist – he’d study how many rings were around the can, whether it was a gold label or a silver label and then he would shake it, listen to the sound and spend a couple minutes putting it all together until “Bingo! Beef stew!”

We knew there was no beef stew in there.

There wasn’t anything edible in there, no Spaghetti-Os or anything like that, nothing that you would want to eat. You couldn’t waste anything so once he started opening the can, even if it wasn’t beef stew, you had to eat what was in it – because otherwise you’d be wasting food – and it was always something completely gruesome. We had a limp chicken once, a chicken with its skin coming off and a whole head floating around with staples in its ears; Naaaasty stuff. So I came up with this idea, why not tell the story through a cartoon, have George Liquor serve his kids cans without labels? That’s the origin of this. A lot of the George Liquor stories were kinda based on things that happened when I was a kid, things my Dad did.

So begins the most recent in a long string of unique and compelling animated projects undertaken by John Kricfalusi, the man possibly best known for his distinctly intense contribution to children’s television culture The Ren & Stimpy Show, back in 1991. Despite the show’s notoriously tumultuous production, it has remained one of the most commonly cited influences for a whole generation of cartoonists, illustrators and animators, with a ripple effect that has changed the landscape of TV animation. Since then he has forged a highly reputed career directing commercials, music videos, TV spots, TV specials and as one of the key pioneers of web-based Flash animation, with online serials The Goddamn George Liquor Program and the evocatively-titled Weekend Pussy Hunt for Icebox. The titular lead of the former (voiced by Michael Pataki who unfortunately passed last year) has been a mainstay of the Kricfalusi universe since the early days of pitching Ren & Stimpy, so it’s fitting that he take the lead in this latest film. Having been put on to the concept of crowdfunding through friends (including The Pig Farmer director Nick Cross, who had found success through it), Cans Without Labels is John K’s first such stab at turning to a prospective audience for funds.

I didn’t think people would actually pay for anything on the internet, because for years people were allergic to that, they wanted to bootleg everything. So I’ve finally tried it, and I’m amazed at how it’s doing pretty well. This is a way to be direct with the audience, just give them what they want and not have a bunch of people second-guessing everything you do.

It is this direct communication that holds the most appeal, as it has the potential to determine the direction and artistic progression of not just this current project, but those to come down the line.

An entertainer is gonna listen to the audience, right? If you’re a standup comedian and you go up and tell a bunch of jokes that you thought were hilarious, and there’s crickets…well, you’re gonna revise your routine. It’s a little harder to do that with animation, because you can’t do it live, but crowdfunding is the best invention ever for entertainers, I think.

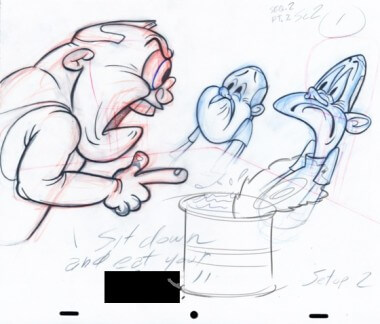

Layout for “Cans Without Labels”, ©John K

Favouring the traditional process of hand-drawn, 2D animation over CG, the film’s layouts have been rendered in pencil, with the planned animation to combine ToonBoom and Cintiq.

It’s still traditionally drawn, not just moving a cutout across a screen; There are a lot of drawings in there, all hand-drawn, so it’s traditional in that sense. We colour the characters on the computer – nobody can do cels anymore, it’s too expensive. I love real painted backgrounds. I might do some of those in this cartoon, if we get the budget we need then we’ll maybe hire some of the ‘Ren & Stimpy’ background painters to do some of those traditional, beautiful backgrounds.

We had a really elaborate system when we were first doing the Flash cartoons: Drew everything in pencil, inked it, but once we turned it into vector art, it would destroy the lines, make them look weird. So we had to add a step called ‘Optimisation’ where I had a whole army of people who would take the screwed-up vector lines and move those little points around to make it look like the original. That was expensive and time-consuming – and irritating – but I don’t have that problem anymore, I can just draw in ToonBoom. The brush is so good in ToonBoom that when I do a line it’s like a finished ink line, it eliminates all the stages in between the pencil line and the inking. Not only is it faster, it looks better.

As well as being assisted by recent protégés John Kedzie and Sarah Harkey, the film will also be an opportunity for a number of talented animators to learn the art of animation from the man himself. Known as something of a talent scout, Kricfalusi has invoked the spirit of cartoon production from the thirties and forties – a model he strongly advocates, and one that he enthuses allows young talents far more scope for personal and artistic growth than the current methods of most major networks and studios.

©John K

If you go to the Nickelodeon website – probably the other networks too – and you want to get a job, they ask for your résumé! Who gives a crap about a résumé in a cartoon studio? You look at their portfolio! And you don’t have some executives look at it, you need an experienced artist who’s in production on a cartoon, who can tell not only if the person has artistic skill, but if they fit your style. Unfortunately there are no animation schools that I know of that teach the fundamentals of what will make you a really good animator. So I kinda have to show them “Stop using these formulas you see in modern cartoons and try to think more, try to get down your personality, then you should be able to put yourself into other characters’ personalities too”. A lot of animators don’t draw their own personalities, even if they’re really good – they draw what they think animation is supposed to be. I’m totally opposed to that.

Cans Without Labels will run at approximately the same length as the average Ren & Stimpy episode (eight-to-ten minutes long) and production is tentatively expected to last roughly seven months after the funds are secured. After completion its future and visibility is not yet certain; one assumes that, as with its creation, the audience itself will play a pivotal role in it’s distribution.

I’m not even sure if you need a distribution deal. When you send it to the people who helped you make it, it’s gonna be online, there’s nothing you can do about it. You can hope that it’s not gonna end up on YouTube, but already all my old George Liquor cartoons, they’re all on YouTube, somebody keeps putting them up! So there’s no way to stop that but maybe it doesn’t matter, because if you’re getting your stuff funded by the audience then you stay in business.

George Liquor: A MANLY History

A “George Liquor” model sheet

George Liquor goes back to the same time I created Ren & Stimpy, about 1980. Bob Jacques (a great animator from Canada) and I were just driving through Van Nuys, long before we ever actually animated Ren & Stimpy. We drove by a liquor store that had this giant neon sign that said ‘George Liquor’! And I screamed, “BOB! Stop! Look!” I jumped out, took a picture of it and quickly sketched up this bug-eyed guy with buck teeth and a shotgun out in the middle of the forest, beer cans littered all over the floor, shooting up the whole wilderness. That was the birth of George Liquor, it was actually the only time I ever instantly thought of a character, knew exactly what he looked like and knew everything about him. So he was one of the original characters in the original Ren & Stimpy pitch – he was their master. One of the first stories I wrote was called Wilderness Adventure and it was where George Liquor takes Ren and Stimpy out to the wilderness. So he takes them out into the woods and they rough it for, like, five days, George just completely loves it. Ren hates it, Stimpy loves it, because Stimpy only has one nerve-ending, so he doesn’t really feel pain or anything like that. So that was one of the first stories that I pitched to all the Saturday morning cartoon networks. They all thought I was crazy, I actually got thrown out of NBC one time, they got the security guards to haul me outta there! They’d never seen anyone get excited over a pitch, I guess.

He’s like the American version of my Dad, who’s a really manly, Canadian man. I guess because he’s human he has more of a backstory. I don’t always use it, I just kind of know it. He’s from the greatest generation; George was part of a war where the Americans wanted to steal the Canadian beer, because Canada had much better beer resources than America does – American beer tastes like piss, Canadian beer is the real thing, that’s a man’s beer.

George’s neighbourhood is called Decentville, it’s the last decent place in America that isn’t corrupted by modern culture and ‘the internets’. Decentville is right on the border between Canada and the United States, and there’s a big fat dotted line on the map with bushes all around that George is always peering through to see what those ‘dirty communists’ are doing in Canada. But really he just wants to sneak across and buy some Labatt’s 50, which is the world’s most manly beer. You can’t even get it in the United States. It’s too manly.George as Ren & Stimpy’s master in “Dog Show”

They hated him at Nickelodeon. They loved Ren and Stimpy, and they liked Mr. Horse, but they hated George Liquor. So all through the first season I wasn’t allowed to do any of the George Liquor cartoons, Jim Smith did this magnificent, epic storyboard for Wilderness Adventure and they rejected it. We couldn’t figure it out, it was one of our best storyboards, but they just didn’t like the character. For some reason they thought George Liquor was a threat to everything that they held dear and they didn’t get the satire. George Liquor’s a little bit like Archie Bunker in All In The Family (the US equivalent of Alf Garnett in Till Death Us Do Part, for UK readers), it’s not really condoning Archie’s behavior, it’s making fun of it.

I talked them into using George in the second season. There was Dog Show, which they weren’t crazy about but they aired it, and then we did ‘Man’s Best Friend’, which was my favourite. That one they just couldn’t handle, even though they approved it at the storyboard stage, once the film came back it was too intense. I guess it’s not the same thing to read the storyboard as seeing the finished film. So they rejected it and wouldn’t run it, it was banned for years and years. I used to run it at festivals and comic conventions and stuff, movie theatres, and people always went nuts.

Still from “Man’s Best Friend”

There’s a scene near the end where, sort of as an homage to Raging Bull, Ren hits George with an oar. It’s really good animation by Kelly Armstrong and when it runs in a movie theatre, people stand up right in the middle of and just start screaming! The funny thing is, the parts that the network hated the most are the parts where the audience cheers! It’s just amazing how networks really don’t have a connection to the audience, really don’t know what the audience likes, and they keep handicapping the creative people who live to entertain an audience. That’s why this Kickstarter thing is so amazing, we have a complete, direct connection with the audience.

For all their over-cautiousness and reluctance to incorporate Liquor’s farcically abrasive and staunchly Republican persona in a family show, Nickelodeon’s fears proved largely unfounded. Episodes such as Stimpy’s Invention, which had narrowly avoided the axe, proved to be fan favourites. In fact, the show’s frenetic energy and adult allusions far from limited its audience; if anything, such qualities gave it further reach.

There was only one bad review and it was before the cartoon ever came out. I think Nickelodeon, when they were first starting Nicktoons, would show some excerpts to the press before they actually aired the cartoons. There was one lady who wrote just a little article in the newspapers, who was horrified. So we were really nervous when the show came out, we thought “Oh man, we’re gonna get skewered, all the parents’ groups are gonna be after us, all the religious groups are gonna wanna lynch us” – and, surprisingly, when the show came out it was the opposite. We got a million letters – not just from the kids, we had parents, priests, gay couples saying “We really identify with Ren and Stimpy”! It pretty much ended up being a family show without trying to be.

The original “Ren & Stimpy” title card

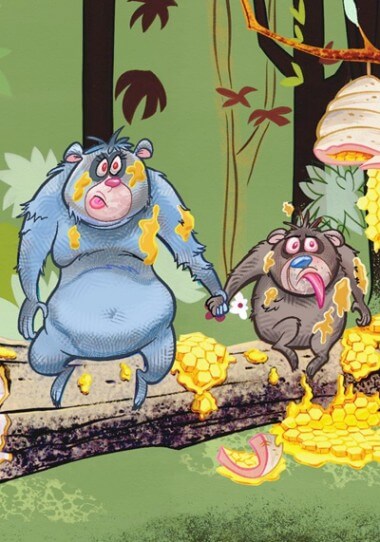

After roughly two seasons, the show was taken out of Kricfalusi’s hands in a move that was so divisive and highly publicised that it nowadays lends itself in part to pop culture apocrypha. While he would eventually reclaim the rights to the show’s main ensemble cast a decade later, he was free to keep George Liquor and a host of characters both original and iconic for the variety of projects he took on in the interim. These included music videos for the likes of Björk, Tenacious D and “Weird Al” Yankovic, television bumpers, commercials and the aforementioned web serials whose added interactivity foreshadowed our current animated app culture. Some of his most satisfying work during this period came in the form of a series of TV specials for Cartoon Network that afforded him the opportunity to take on characters from the ‘Yogi Bear’ and ‘Jetsons’ universe with no restrictions, such as the joyfully surreal A Day in the Life of Ranger Smith and fan-favourite Boo Boo Runs Wild.

Art from “Boo Boo Runs Wild”

When I was growing up, I taught myself to draw watching Hanna Barbera cartoons – they were easier to draw than Bugs Bunny or Tom and Jerry. The early Hanna Barbera cartoons were completely character-driven, because they didn’t have the budgets to do full animation. Tom & Jerry cartoons were lushly animated, beautiful full animation, but really expensive to make. If you wanted to get cartoons on TV the budgets were one-tenth of that, so instead they changed the focus from the animation to personality, relying almost exclusively on the way the characters looked and sounded. They were designed by Ed Benedict, who had a really appealing design style and made the characters look great. I started writing my own stories with them and doing my own weird caricatures of those characters, where I’d take their basic personalities and designs and exaggerate them. Well, that’s what I did with the Hanna Barbera cartoons that I did in the nineties for Cartoon Network, and that was really fun. I wasn’t necessarily making fun of the characters, it was taking what was already there and then just pushing it further, making it more extreme, like I did with ‘The Simpsons’.” Said contribution to the world’s most notorious animated family sitcom came in the form of his own signature ‘couch gag’ to cap the opening credits of a recent episode. “Al Jean emailed me, said he and Matt had been talking about asking me to do a couch gag in my design style, so I went down to Fox and had lunch with them, did a bunch of sketches with them there. We thought up the idea together, and they just said “Do it off-model, do it your way, exaggerate it and just have fun with it”. It was a riot to do. I only had thirty seconds – it was just a couch gag – but I took their basic personalities and really distilled it so I could tell it fast.

Prior to this, the only guest artist to make such a contribution was Bristol’s own Banksy, whose concept was animated by the existing Simpsons animation staff. In Kricfalusi’s case, he was granted full reign of the animation itself (setting a precedent for subsequent guest animators, including Bill Plympton earlier this year).

Originally they thought if I just storyboarded it then they would give it to their animators, but because they’re so used to drawing everything on-model, even if I gave them a crazy-looking storyboard they’d tone it all down and nobody’d ever know that I had anything to do with it. In Banksy’s case it was funny, really funny, but I wouldn’t have known it was Banksy if they hadn’t told me. We just took it a step further and made it look like I did it, which I think was fun.

The vignette doesn’t waste a frame of the thirty seconds allocated, and probably warrants the most repeat viewing of any of his recent work in order to fully imbibe the level of effervescent detail that went into it.

I love the old cartoons because you can tell one animator from the other. Chuck Jones’s cartoons look different from Tex Avery’s cartoons, even if they’re both doing Bugs Bunny, they look different and have their own personality. I tried to stick with the characters’ personalities. I think the one that I changed was Marge – I was inspired by the way the Fleischers animated Olive Oyl, the crazy arms and legs and everything, I wanted to try something like that with Marge. So I didn’t really follow her personality, I just made her crazy. But Homer’s pretty much Homer, just a distilled version of him; just wants his beer, wants his wife to be subservient…

Alongside his career – and in many respects a significant contributor to his current reputation as, among other things, a bona fide animation historian – Kricfalusi has been an active blogger, with his website ‘John K Stuff’ a smorgasbord of animation theory, tutorials and critical dissections of both classic and contemporary cartoons (naturally it is also the first port of call to stay updated on his personal projects and work commissions). For over six years blogging has been a culture he is both a participant and fan of.

I think the blog revolution really did some great stuff for animation, it probably does it for every medium. Steve Worth has a great animation archive blog, there’s so much information now online. Not just about animation that everybody already knew about, like Disney, but stuff that’s been forgotten: Great old comic books, a hundred years’ worth of comic strips, all this stuff is available to young cartoonists who need inspiration. When I was a kid it was really hard to find any information on animation, now all the information that you would ever want about cartoons, comics, illustration, it’s all available online. It should cause a renaissance of cartooning for the next generation, because there’s so much information to pull from now.

I mean, it’s a visual medium – it’s the most visual medium, even more than live-action. Even old, classic live-action movies, most of the directors were artists – Jon Ford, John Huston, these old directors were artists, they really were visual people, and in cartoons it’s even more so. Everybody in a cartoon production in the 1930s to the 1950s was an artist. They didn’t even use scripts, if you went to Walt Disney and said “Hey, I’ve got this great script for a cartoon” he’d look at you like you were crazy. This is animation, you have animators with a story sense write the stories on storyboards. As soon as scripts took over the animation business, it was kind of the end of the visual part of animation, and since the sixties it’s just become more and more inbred.

Consequently, the animation industry Kricfalusi entered in the late-seventies was far from creatively satisfying. Describing the process of television animation as “a weird, factory assembly-line system”, it was the separation of storyboard artists and writers along with the fundamental absence of a discernible director that fragmented the animation process for mass-marketed series. After the mid-eighties, some reprieve came in the form of collaboration with independent hero Ralph Bakshi, the director behind such controversial features as Coonskin and the feature adaptation of R. Crumb’s Fritz The Cat. Together, however, it was the duo’s revival of ‘Mighty Mouse’ in 1987 that put the wheels in motion for a reversion to old practices.

Bakshi’s Mighty Mouse was the beginning of bringing back the old unit system where one person would oversee the cartoon from the beginning idea all the way through to the finished soundtrack. I love the old studio system, if you look at old cartoons from 1938 or 1939 the animation is just leagues ahead of anything anybody does today, because all the animation was done in-house and everybody knew each other and they all evolved. With trial, error and practice they went from Steamboat Willie in 1928 to Snow White in 1937 – in nine years! The system we have right now doesn’t allow for that, because all the animation is done overseas or it’s done in Flash, budgets are too low, and networks now have this crazy idea in their head that every series should come from somebody who has no experience, just a ‘great idea’. In the old studio system the animators worked their way up, you didn’t start as a director. Bob Clampett jumped out of high school, he was sixteen years old when he started as an in-betweener at Harman & Ising. That’s the absolute, best way, start as an in-betweener working for an experienced animator, so you learn from the animator. Then, if you’re good enough, they’ll promote you to animator, and then you’re really starting to understand how the medium works. If you’re a really funny guy and you know how to animate, they move you over to the storyboard department and you start writing stories. When you’re writing the stories you now know how animation works, so you gear your stories to take advantage of the process of animation. If you’re good at story, a good animator and you’re good at personality, there’s a chance you’ll be a good director. I’m sure when I was sixteen I thought I could direct, but I didn’t start directing for real until I was about twenty-eight, on The New Adventures of Mighty Mouse. When that came out, it was a complete revolution, different from everything else in Saturday morning cartoons.

While this served to be a boon to subsequent animation in a lot of respects, shortly after the era of Ren & Stimpy the process adapted once more, with the reclamation of creator-driven properties eventually losing its original meaning.

It’s the fault of the Hollywood system, the network system …it’s actually partly my fault (laughs) because when we did Ren & Stimpy and when Klasky Csupo did ‘Rugrats’, these were the first cartoons in fifty years that were creator-driven. The creators were actually writing the stories and directing the cartoons, which were so successful that the creator-driven model all of a sudden became trendy, and the networks started thinking that instead of getting experienced people they had to get the next young person who hadn’t been spoiled by the business. So that creator-driven thing has kinda degenerated over the years to really primitive, amateurish-looking stuff on TV.

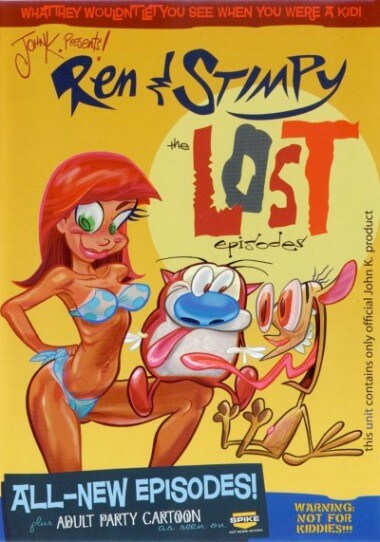

Kricfalusi himself has returned to episodic TV on occasion, collaborating with Jim Smith again for The Ripping Friends in 2001 and rebooting Ren and Stimpy for the short-lived Adult Party Cartoon, a series that fared better on the DVD market, renamed The Lost Episodes. The show boasted, in many respects, some of the most ambitious and considerate animation direction of his career, but replacing the adult allusions of the original show with purposefully explicit content proved somewhat controversial, (leading to a fascinating public exchange between himself and fellow historian Michael Barrier debating what the show set out to achieve). The one constant of his work, whether to an audience’s tastes or not in terms of subject matter, is the consistently high artistic standards that span layouts, backgrounds, storyboards and, of course, the animation itself. Regrettably, as documented recently on Cartoon Brew, a highly anticipated Art of Spumco book that would have chronicled the wealth of artistic talent shared by Kricfalusi and his peers was stymied and may possibly remain in limbo indefinitely.

Kricfalusi himself has returned to episodic TV on occasion, collaborating with Jim Smith again for The Ripping Friends in 2001 and rebooting Ren and Stimpy for the short-lived Adult Party Cartoon, a series that fared better on the DVD market, renamed The Lost Episodes. The show boasted, in many respects, some of the most ambitious and considerate animation direction of his career, but replacing the adult allusions of the original show with purposefully explicit content proved somewhat controversial, (leading to a fascinating public exchange between himself and fellow historian Michael Barrier debating what the show set out to achieve). The one constant of his work, whether to an audience’s tastes or not in terms of subject matter, is the consistently high artistic standards that span layouts, backgrounds, storyboards and, of course, the animation itself. Regrettably, as documented recently on Cartoon Brew, a highly anticipated Art of Spumco book that would have chronicled the wealth of artistic talent shared by Kricfalusi and his peers was stymied and may possibly remain in limbo indefinitely.

I collect ‘Art of’ books and I’m always frustrated that there’s usually not much art in them. It’s all text or white space. In the last twenty years a new job category has been invented – ‘book designer’, whose goal is not to showcase the art, but to showcase his design. This was going on with my book; I told them from the beginning I only wanted to do it if I could actually give the audience what they’d be buying the book for – the art. So many of these beautiful backgrounds by Bill Wray, Scott Wills, Vicky Jensen, all these great layouts and storyboards from Jim Smith, Bob Camp, Bruce Timm, all these artists that people love, that’s what they want. They promised me in the beginning, “Don’t worry John, we’ll do it just how you want it”. And then they had me write a book that was like a thousand pages, every time I’d write something they’d want me to elaborate on the story. Amid (Amidi, the book’s editor) was very helpful, because when you’re writing stream-of-consciousness you make a lot of mistakes, or you’re redundant. It’s very hard to be objective about your own writing, and he would catch all that stuff and remind me of stories that I had forgotten, some stuff that he’d witnessed when he used to work at Spumco. So Amid was great, it was the publisher and book designer who had no design sense whatsoever!

Proposed spread layout for the unreleased “Art of Spumco” book

When they started to lay it out they did exactly what I’d said I didn’t want – tons of dead white space, you couldn’t even believe it. Nobody wants to pay for blank paper! Anyways, I think that’s why books are done, because they won’t give people what they want.

While on the surface such an outlook seems bleak, it’s also indicative of a cultural shift already underway, one that might allow the work to be seen in an alternative context:

A lot of people are asking me “Why don’t you publish it on Kickstarter?” because I know a couple of self-publishers who do really nice art books. I have tons of artwork, maybe I’ll just do an art book that has no text in it except the credit of who the artists were, and then put all the story stuff online for free. You buy a book and you get a code, if you wanna read the backstories, find them!

Until such an idea sees the light of day, fans are able to appreciate the regular showcase of past artwork online, as well as what’s sure to be an exciting future that may very well redefine the relationship between creator, creation and audience. In the meantime, what of a possible third incarnation for the venerated Asthma-Hound Chihuahua and feline duo that began it all?

There are all kinds of episodes that we wrote and storyboarded and are ready to go, but unfortunately Spike only ran two or three episodes before they stopped. Had they gone into a second season, we’d probably still be doing ‘Ren & Stimpy’ by now. Whoever’s at Nickelodeon and Viacom now had nothing to do with the original show, so I don’t think they’re gonna be that interested in reviving it. But I have a million other characters, I’ve got this character called ‘He-Hog: The Atomic Pig’, a superhero pig. It’s a spoof on superheroes, not just a generic spoof, it’s much more about the characters than it is about the genre, although there’s a lot of genre jokes in it. People who read superhero comics will love it. We do a lot of visual gags that come out of the personalities, it’s not just written gags.

I’m also dying to do more toys and I’m thinking maybe Kickstarter’s a way to do that, too. I’m starting to see that the art of crowdfunding is kinda the art of the rewards, not just the product that you make. So next time around I wanna put some of the money into creating custom toys and rewards – really cool, funny stuff that you couldn’t get in the stores. Dealing with stores is the same thing as dealing with networks, they have a million preconceived rules about what sells and what doesn’t, and they really have no concept whatsoever what people like, so again I’m hoping that with direct access to the audience, you can make things that people like and find out right away if they want you to make them. If they do, then they pay for them – sounds like a great system to me!

John Kricfalusi’s short ‘Cans Without Labels’ is accepting donations until August 17th, 15:39 EDT (20:39 UK time). Incentives include doodles, Spumco membership kits, toys, storyboard art, t-shirts and, for the high-rollers, animation cels and background paintings! To check out all that’s on offer visit the film’s Kickstarter page, as well as John’s regularly-updated blog.